During the 1800s and early 1900s, the Brooklyn Navy Yard served as a pseudo receiving and distributing station for the animal mascots of American warships.

Some of these animals, like Tom of the USS Maine, were born at the Navy Yard, while others stopped in to visit from time to time during their many years at sea.

In the late 1800s, an Italian-American sailor named Cosmero Aquatero was working as a barber on the USS Vermont, which was permanently anchored at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. During his years stationed in Brooklyn, he kept a record of the births and major events in the lives of these mascots in a dilapidated old book.

In March 1898, a reporter from The World interviewed Aquatero about some of the famous ship mascots.

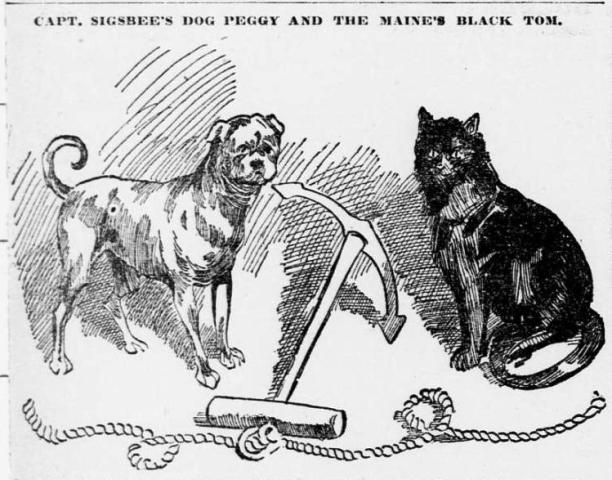

Two of the mascots that were well documented in Aquatero’s book were Tom, the mascot of the infamous USS Maine, and Peggy, the young pet pug of the ship’s captain.

As two of the only 91 “crew members” who survived the massive explosion on board the Maine in the Havana Harbor in 1898, their lives were pretty incredible.

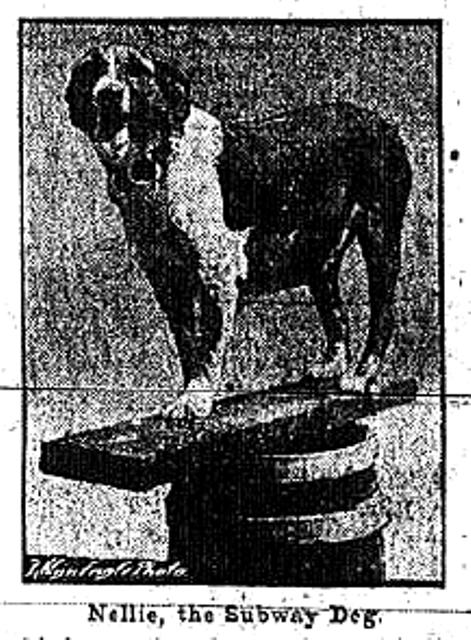

Tom, the Senior Navy Cat

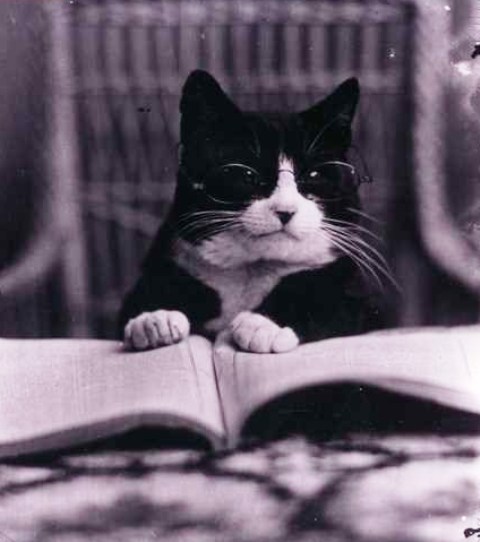

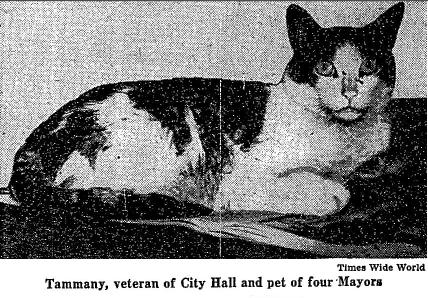

According to Aquatero’s records, Tom was born at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1885 (an article in the St. Paul Globe says he was born on a farm in Pennsylvania, but I prefer to trust the old sailor). A grey and black tabby, Tom was very much respected by the sailors, who believed cats brought good luck to ships. There wasn’t a sailor throughout the world who hadn’t made his acquaintance over the years, and each mariner that sailed with Tom placed his greatest confidence in the cat.

Tom began his Navy career on board the USS Minnestota, but when an officer from that ship was transferred to the Maine, he brought Tom with him. On board the Maine, it was Tom’s job to get rid of the rats and the mice. However, it seems that one time the cat was trained to coexist with a rat named Christopher, which had been adopted and tamed by one of the ship’s sailors. As the story goes, cat and rat were able to stay in a room together, but they never did become good friends.

By 1898, when the USS Maine exploded in Havana, Tom was still an active member of the crew and considered to be the oldest cat in the United States Navy.

Peggy the Pug

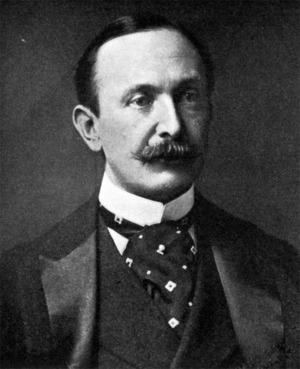

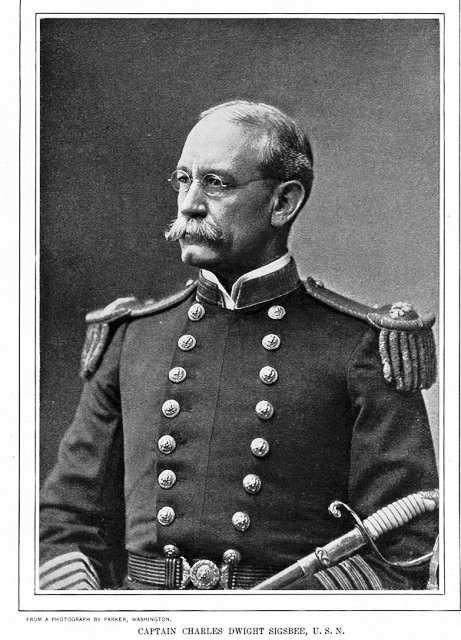

Peggy was the pet of Captain Charles Dwight Sigsbee and his wife, Eliza Rogers Lockwood Sigsbee. The young little dog followed the captain all over the ship, no matter how many steps or ladders he climbed – one time she even fell and broke her leg while following him up a ladder. Peggy was suspicious of everyone in civilian dress that came on board the USS Maine, and barked at anyone who was not in uniform.

In 1898, when the USS Maine disaster occurred in Cuba, Peggy was not quite two years old.

The USS Maine and the Battleship Era

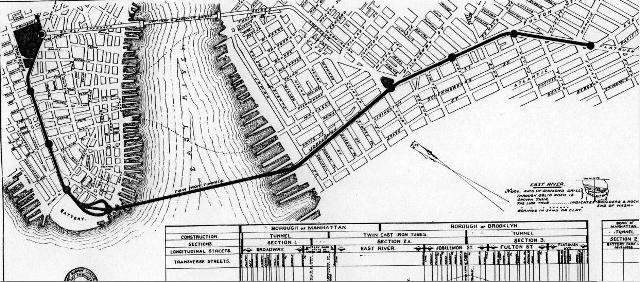

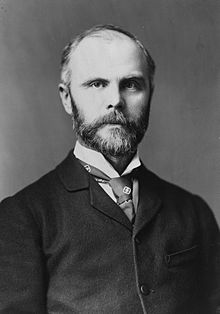

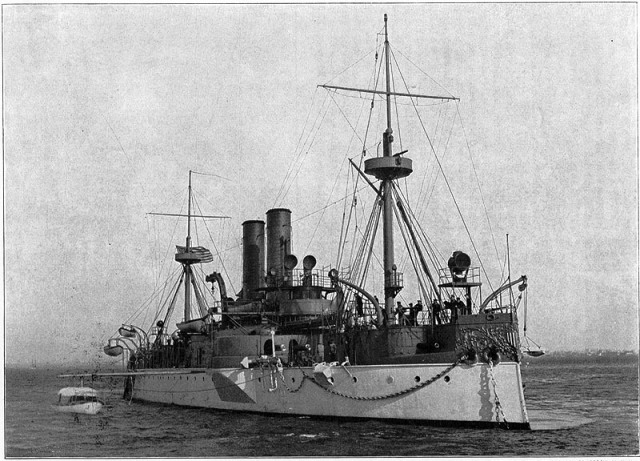

The USS Maine and her sister ship, the USS Texas, were the first modern warships built in the United States. They were built in response to the growing naval power of Brazil, which had commissioned several battleships from Europe, most notably the Riacheulo in 1883.

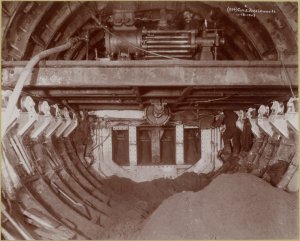

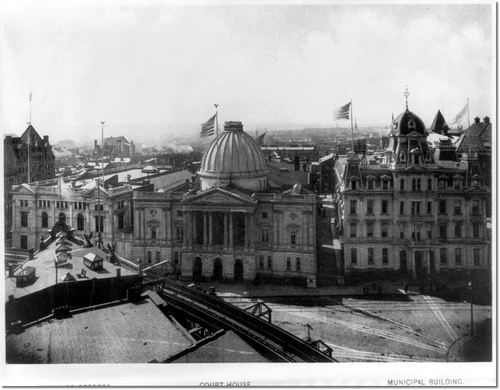

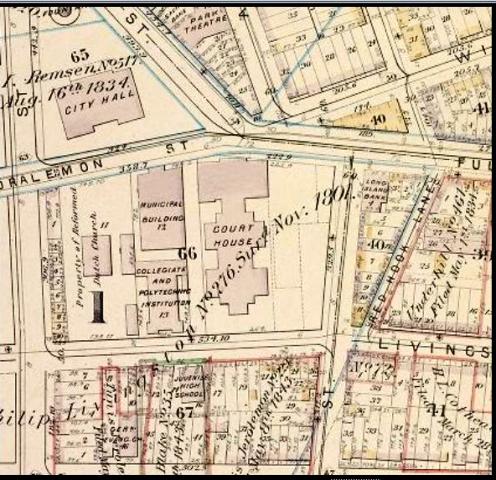

In 1886, Congress authorized the construction of the Maine and in 1888, her keel was laid down at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The 6,682-ton, steel twin-screw battleship was launched from the yard on November 18, 1889. The launch of the USS Maine officially began the “battleship era” for the United States.

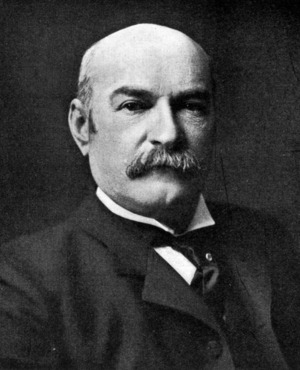

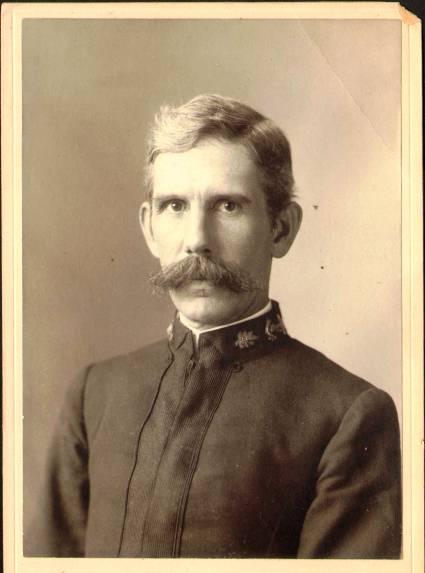

Due to some equipment setbacks, the USS Maine was not commissioned until September 17, 1895, under the command of Captain Arent S. Crowninshield. The ship spent most of her active career with the North Atlantic Squadron, operating from Norfolk, Virginia, along the East Coast and the Caribbean. On April 10, 1897, Captain Sigsbee relieved Captain Crowninshield as commander of the

USS Maine.

Remember the Maine!

In January 1898, the USS Maine was sent from Key West, Florida, to Havana to protect American interests during the Cuban War of Independence. Three weeks later, at about 9:40 p.m. on February 15, a massive explosion ripped through the forward section of the ship.

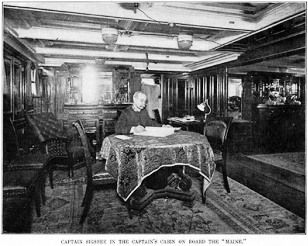

Most of Maine’s crew was sleeping or resting in their hammocks in this part of the ship when the explosion occurred. Captain Sigsbee and most of the officers, on the other hand, were in their staterooms or their smoking quarters, which were in the aft section of the ship.

Peggy and Tom Survive

When the explosion occurred, Peggy the pug had been asleep in Captain Sigsbee’s stateroom. The captain was also in his cabin and placing a letter in an envelope at the very moment the explosion came. As the captain reported in The Century Magazine, there was a trembling and lurching motion of the vessel, and all the electric lights went out. Then there was intense blackness and smoke.

Somehow Peggy managed to find her way to the poop-deck, which was the highest intact part of the ship above water. There, the captain and Commander Richard Wainwright were waiting for the battleship to settle on the bottom of the harbor. Peggy, trembling with fright, reportedly stood at the place she was taught to take when the lifeboats were lowered.

Crews from nearby ships, including the Alfonso XII and the City of Washington, manned lifeboats to rescue the surviving crewmen of the Maine. Reluctantly, Captain Sigsbee and Commander Wainwright abandoned the Maine, which continued to burn and explode throughout the night. The next day, Peggy was “strutting about the deck [of the City of Washington] with air of a naval hero.”

Peggy and 62 human survivors returned to Key West on February 17 aboard the steamer Olivette.

Tom’s experience was much more remarkable than Peggy’s, if not miraculous. At the time of the disaster, Tom was sleeping three decks below the upper deck. The force of the explosion was so great that he was literally fired through the three steel decks. The surviving sailors didn’t see Tom at all, and assumed he had perished.

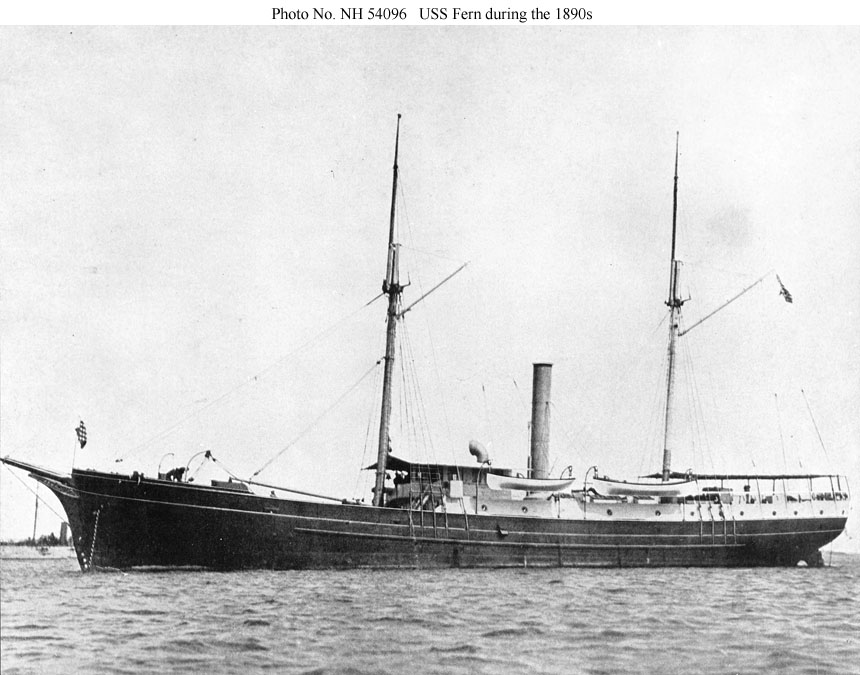

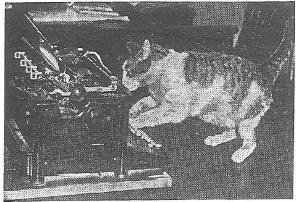

The next morning, Commander Wainwright discovered Tom, who was crying pitifully while crouched on a part of the wreck that was still above water. The officer rescued the cat and took him to the USS Fern, where he was treated for a wounded foot. A few days after the explosion, Tom posed for pictures on a wicker armchair that had been salvaged from the Maine.

Unfortunately, two other cats, including one that joined the ship in Cuba a few days before the explosion, did not survive. However, they did become martyrs for the emerging animal rights movement in the United States. (Animal rights groups often pointed to the Navy and its sailors for their humane treatment of animals as a model for the rest of the country.)

In a pro-cat book published by ASPCA, the author hailed the two cats who died for their country: “The love of cats by sailors and soldiers is well known. In the dreadful explosion of the Maine in Havana, two of the three cats perished.”

In total 260 men lost their lives as a result of the explosion or shortly thereafter, and six more died later from injuries. There were only 89 survivors, not counting Peggy and Tom, 18 of whom were officers. On March 21, 1898, the US Naval Court of Inquiry declared that a naval mine caused the explosion.

A second forensic inquiry was conducted by Admiral Hyman Rickover in 1974, which confirmed that the cause of the Maine’s destruction was not a Spanish mine or bomb, but the detonation of the forward gun magazines.

Peggy the Pug Perishes

After spending time in Key West for some much-earned rest and relaxation, Peggy was given to U.S. Naval Commander J.Y. Wynn, who was stationed in Chelsea, England.

Soon after moving in with his family, she was outside playing when she either fell or jumped into a catch basin on Addison Street. Efforts were made at once to save her, but she was smothered before they could get her out. Peggy was taken to the Commander Wynn’s home for burial.

If it was fashionable in Paris, it was a fashion must in New York. Extravagant hats with ostrich feathers and outrageous fur muffs and shawls were in high style in the 1800s.[/caption]

If it was fashionable in Paris, it was a fashion must in New York. Extravagant hats with ostrich feathers and outrageous fur muffs and shawls were in high style in the 1800s.[/caption]