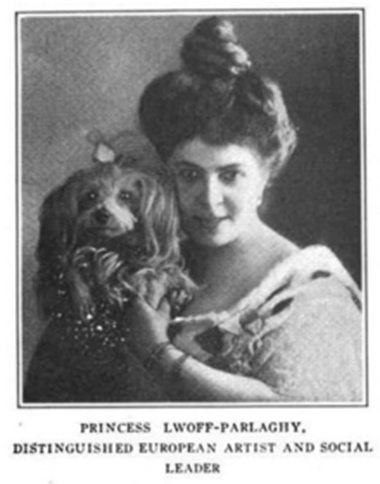

Once upon a time – June 1908, to be exact – an eccentric pseudo-princess portrait painter named Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy came to New York City. This beautiful auburn-haired princess loved all kinds of animals and despised people who were not kind to them.

She told the press (via her private press secretary, Frederick M. Delius) that she lived by the motto, “Love me, love my dog.”

Perhaps her motto should have been, “Love me, love my dogs, my cat, my guinea pig, my alligators, my owls, my pelican, my monkey, my snakes, my bear, my falcons, my wolves, my ibis, and my lion cub.”

Her Supreme Highness, Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy (as her servants called her), was born Elisabeth Vilma von Parlaghy in Hajdúdorog, Hungary, on April 15, 1863. Her parents were Baron and Baroness Zollen Dorp of Austria (I’m not sure where Parlaghy comes from).

Vilma began training as a painter in Budapest and Munich in her early teens — she was the only female pupil of Franz von Lenbach — and launched her career as a renowned portrait artist for royalty after painting a portrait of Lajos Kossuth, the former Governor-President of Hungary. One of her most famous and frequent subjects was Kaiser Wilhelm II, German emperor from 1888 to 1918.

It was not her career or family roots, however, that entitled Vilma to call herself a princess. She acquired this royal title through a brief second marriage to Prince George Eugeny Lwoff Wall of Russia, whom she married in Prague in 1899.

(Her first husband was Dr. Karl Kruger, a philosopher from Berlin. She said she divorced him in 1895 because he was too “excitable” for her; other sources say she became too successful for him.)

After traveling to New York in March 1900 so Princess Lwoff could paint Admiral George Dewey, the newlywed couple moved to a villa in Bavaria. The princess, however, soon grew tired of the quiet country life. She divorced the prince in 1903, telling the press that he was too “naughty” for her.

Despite the brief marriage, Vilma decided to keep the name “Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy,” which had been authorized by Prince Lwoff. She also kept a château in Nice on the French Riviera — Chateau St. Jean — that he supposedly gave her.

Following her second divorce, the princess presumably married (or had an affair with) Peter Norsk, a Danish minister. The couple had a daughter named Wilhelmina (Vilma) in 1905 or 1906. The girl spent her childhood living with a governess in London while her mother traveled around the world with her cherished dogs and other pets.

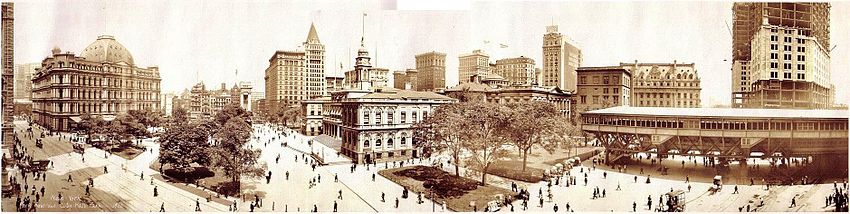

The Princess Goes to the Plaza

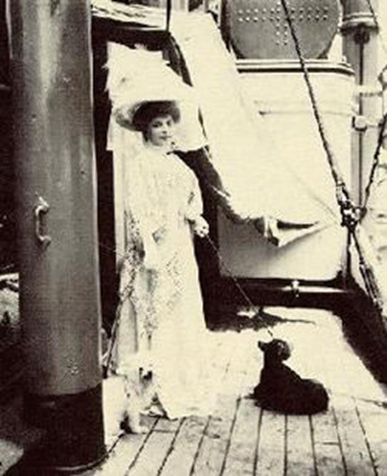

In June 1908, Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy traveled to New York City in order to paint portraits of famous Americans. She was accompanied by “gorgeously uniformed attendants” that included (reports vary on the exact number of servants) two attaches (secretaries), couriers, a footman, three butlers, three maids, a cook, a valet, a bodyguard, and a physician.

She also arrived with her own personal menagerie, including a small Pomeranian dog, an Angora cat, a guinea pig, an owl, an ibis, two small alligators, and a small bear named Teddy.

You can’t make this stuff up.

Although the princess had attempted to find a hotel that would accommodate her caravan of animals (another story about this to come), none of the hotels responded to her letters of inquiry. She apparently tried to stay at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, but the hotel informed her of their pet policy and turned her away — I guess they didn’t accept alligators or bears (or any of the above).

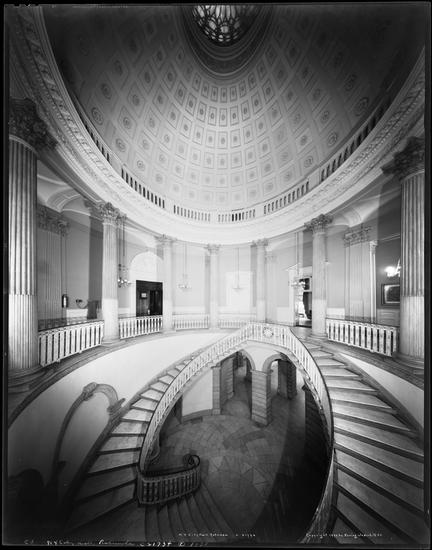

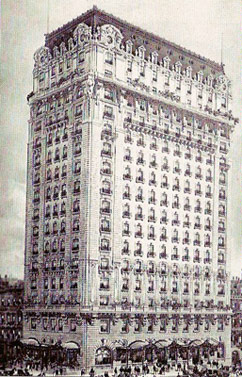

Luckily for the princess and her pets, the brand new Plaza Hotel had an “open door pet policy” that was quite liberal. Arrangements were soon made for a large 14-room suite with private chapel on the third floor of the hotel overlooking Central Park.

For the next five years, Princess Lwoff and her staff called The Plaza their home in New York (at a cost of $25,000 a year). Her staff occupied half the suite, while her extensive menagerie stayed in the antechamber.

The princess had a bedroom that was connected by electric bells to the parlor, maids’ room, and butlers’ room; two additional rooms decorated in Gothic style with stained glass windows served as her studio.

The rest of the suite was a small art museum filled with her expensive potteries, treasured paintings and tapestries, red velvet and gold Louis XVI furniture, and 11th- and 14th-century objects d’art.

(The princess once told a reporter she had to surround herself with millions of dollars worth of art and antiques to stimulate her imagination and give her inspiration to paint.)

The Princess Gets a Lion Cub From Barnum

In early spring 1911, Princess Lwoff fell in love with a newborn lion at the Barnum & Bailey menagerie at Madison Square Garden. She tried for weeks to buy the cub, but the proprietors refused, saying they didn’t want to separate him from his mother. They also said they wanted to keep him because they thought the cub had great potential.

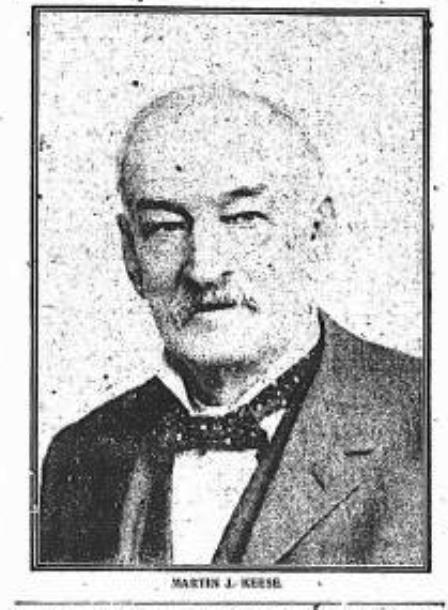

Not about to give in, the princess solicited assistance from General Daniel E. Sickles, whom she had recently painted. The general made arrangements to buy the cub from the circus owners, who apparently could not turn down the great Civil War hero and septuagenarian.

Despite their objection to any payment, he gave them $250 for the cub.

On April 17, 1911, Sickles told the press he was celebrating the 50th anniversary of his going to war by giving the six-week-old cub to the princess. He also said it would be a surprise to her (wink wink).

Princess Lwoff was summoned to Madison Square Garden, and Sickles, still holding the cub, said, “I want you to accept a souvenir of my regard.” She uttered a cry of delight and ordered one of her servants to buy champagne for the occasion. She sprinkled champagne over the cub’s head – I’m sure he loved that – and christened him General Sickles. Then she wrapped him in a woolen blanket, placed him in her car, and drove off in triumph to The Plaza.

The following day, Princess Lwoff sailed for Europe with her entourage and the little cub. While at her studio in Berlin, she painted General Sickles holding the lion in a portrait she called “The Two Lions.”

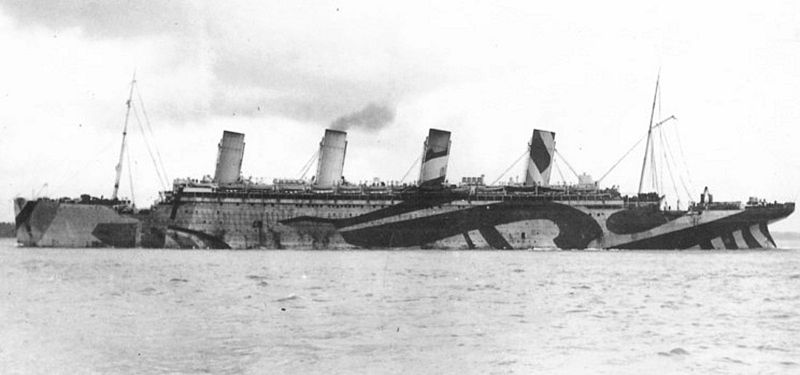

She spent the summer overseas, and when she returned to New York via the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria in October 1911, she announced that the small lion – now named Goldfleck — was as tame as any pet dog, and had been a favorite among hotel guests.

A Short-lived Life at the Plaza

Back at The Plaza, Fred Sterry, the hotel’s managing director, was persuaded to allow Goldfleck use of his own room, with supervision round-the-clock from the cub’s trainer. Apparently there were no complaints, although there was one reported incident involving a poorly timed flash-photograph that frightened Goldfleck, who then raced through an open door and into the public corridors of the hotel, causing a bit of panic among guests and staff members. He was lured back into his room with a piece of raw meat.

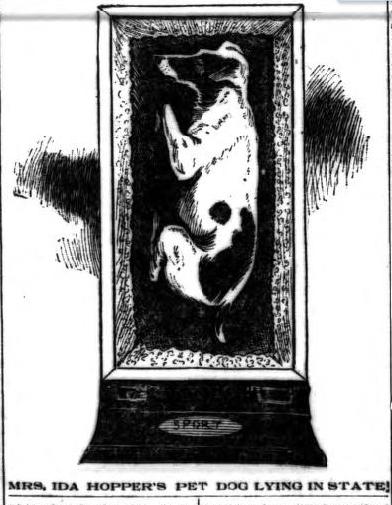

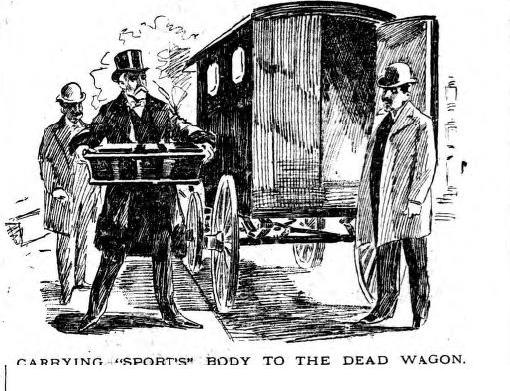

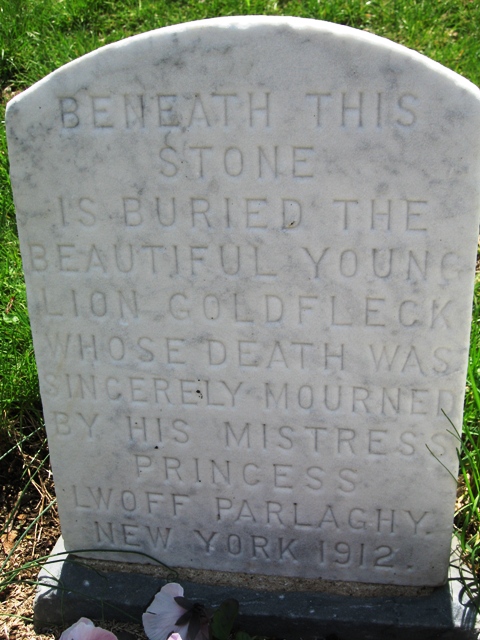

On May 21, 1912, the young lion died at The Plaza. Hotel officials said the cub had never adapted to civilized food and died from gout. The princess held a formal wake in the suite, with the lion covered in elaborate wreaths and surrounded by flowers, toys and dishes.

He was placed in a box and taken by taxi to the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery, accompanied by six cars of mourners.

Her Life After Goldfleck

During World War I, requests for portraits dwindled and Princess Lwoff began living less like a princess and more like a wealthy pauper – if there is such a thing. She was forced to reduce her staff and give up some of her rooms at The Plaza; eventually she had to leave The Plaza because she could not pay her $12,000 bill.

In 1915 the princess moved into a two-room suite at the St. Regis for $20 a day (parlor, bedroom and bath, and no exclusive elevator). She had to find new homes for some of her exotic animals, like the alligators and birds, but she told the press she did keep enough cats and dogs to keep her company at the hotel.

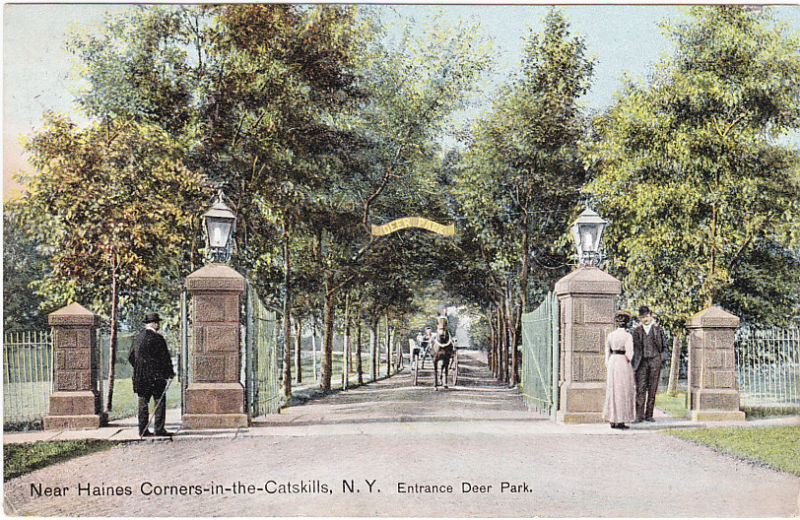

During these hard times, Ludwig Nissen, a retired Brooklyn diamond merchant, agreed to hold four chattel mortgages for the princess on the Catskill estate and a five-story town house on East 39th Street that she moved into around 1916. Alas, when she failed to pay back the $218,000 in mortgages by August 1923, the merchant took action.

On August 26, Deputy Sheriff Joseph A. Lamman arrived at her door armed with three writs of seizure, two detectives from the East 35th Street station, and a locksmith. Although a sign on the iron door said the occupants were away, the princess was home and seriously ill with diabetes.

Her physician told the officers she was in critical mental and physical condition. The princess, surrounded by only her physician, a maid, and Mr. Delius, had barred all visitors from seeing her.

On August 28, 1923, the 60-year-old penniless princess passed away on a golden bed that had once belonged to Marie Antoinette, leaving an estate she would not (and now could not) touch that was valued up to $2 million.

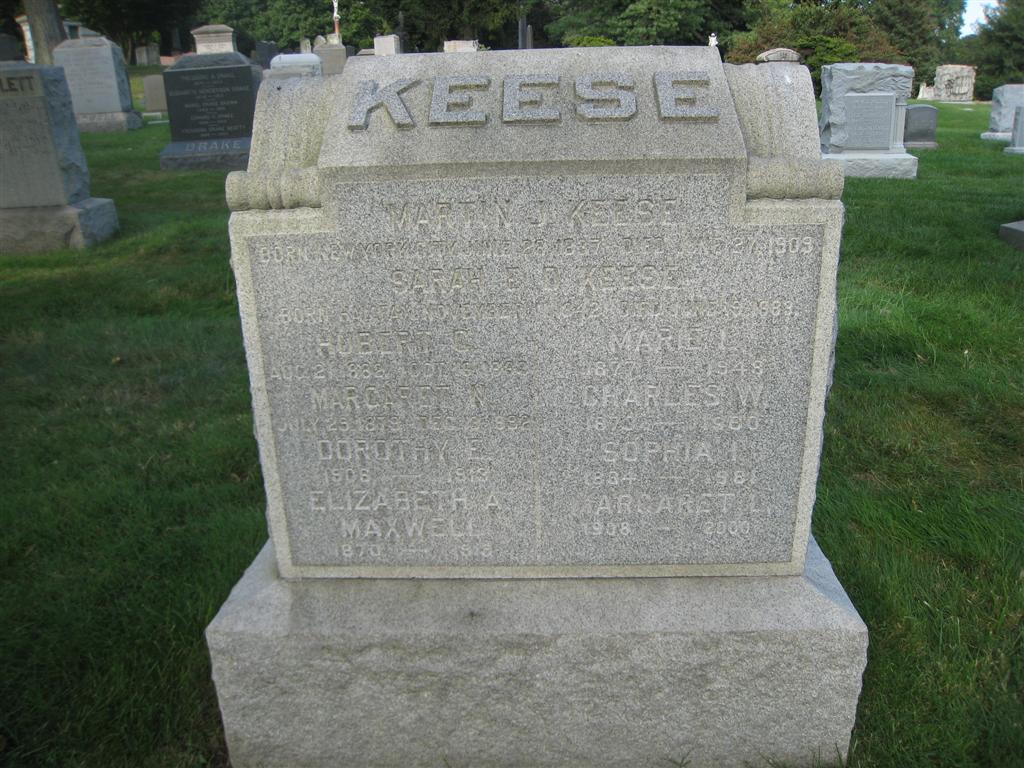

Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, wearing her court robes of blue and gold with a crown of silver and 22 royal decorations. The Poet Laureate Edwin Markham gave her funeral oration. Only her two remaining servants attended the services.