Step back in time 83 years to November 15, 1930. It was on or about this day that a man known only as “Old Tom” passed away in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, leaving his loyal fox terriers behind.

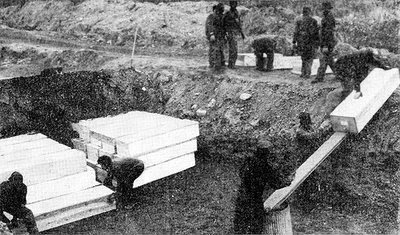

One week after his death, his body still unclaimed at the city morgue, Old Tom’s body was shipped by ferry to Hart Island, where he was buried by inmates from Rikers Island in the country’s largest mass graveyard.

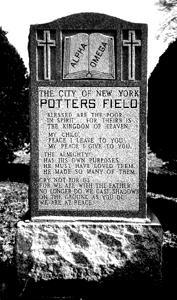

Since 1869, close to 900,000 homeless and poor people, stillborn babies, and unclaimed bodies have been buried without a prayer or eulogy in New York City’s potter’s field on Hart Island. On the anniversary of Old Tom’s death, November 15, 2013, The New York Times published an article about Hart Island, and about the Hart Island Project, a group dedicated to improving access to the 101-acre island and its 45-acre public graveyard.

This Thanksgiving story is dedicated to Old Tom and his fox terriers, and to all the other nameless and unfortunate souls who are interred with him on this island of the dead.

Old Tom and His Fox Terriers

Old Tom was a slight African-American man about five foot seven and 150 pounds. He had what the news reports called a “crippled” right foot and walked with crutches. Old Tom made his meager living doing odd jobs in the tenement buildings on the streets that lie in the shadows of the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges.

Despite his nickname, Tom wasn’t very old: The coroner said he was about 50 when he died from “malnutrition and other causes.” He didn’t appear to have a human family, but he did have two loyal fox terriers and their two newborn puppies to keep him company as he made his rounds along Madison and Pike streets every day.

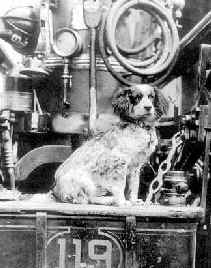

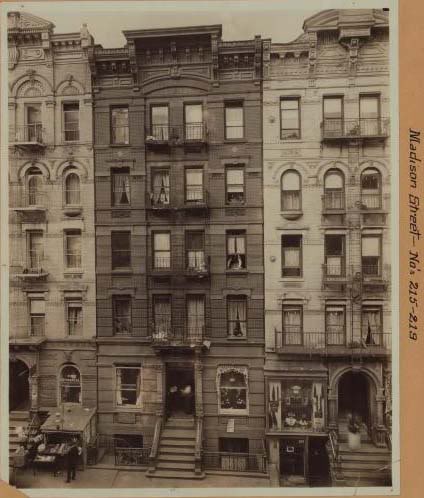

On the Sunday before Thanksgiving, Benjamin Bressman, who was the janitor for the five-story tenement at 149 Madison Street, noticed that Tom hadn’t been seen for almost a week. Apparently Tom had been doing some work in the building, because Benjamin went straight to the basement to look for him. It was there he found Old Tom lying on the cold cellar floor, his crutches at his side, and his fox terriers standing guard.

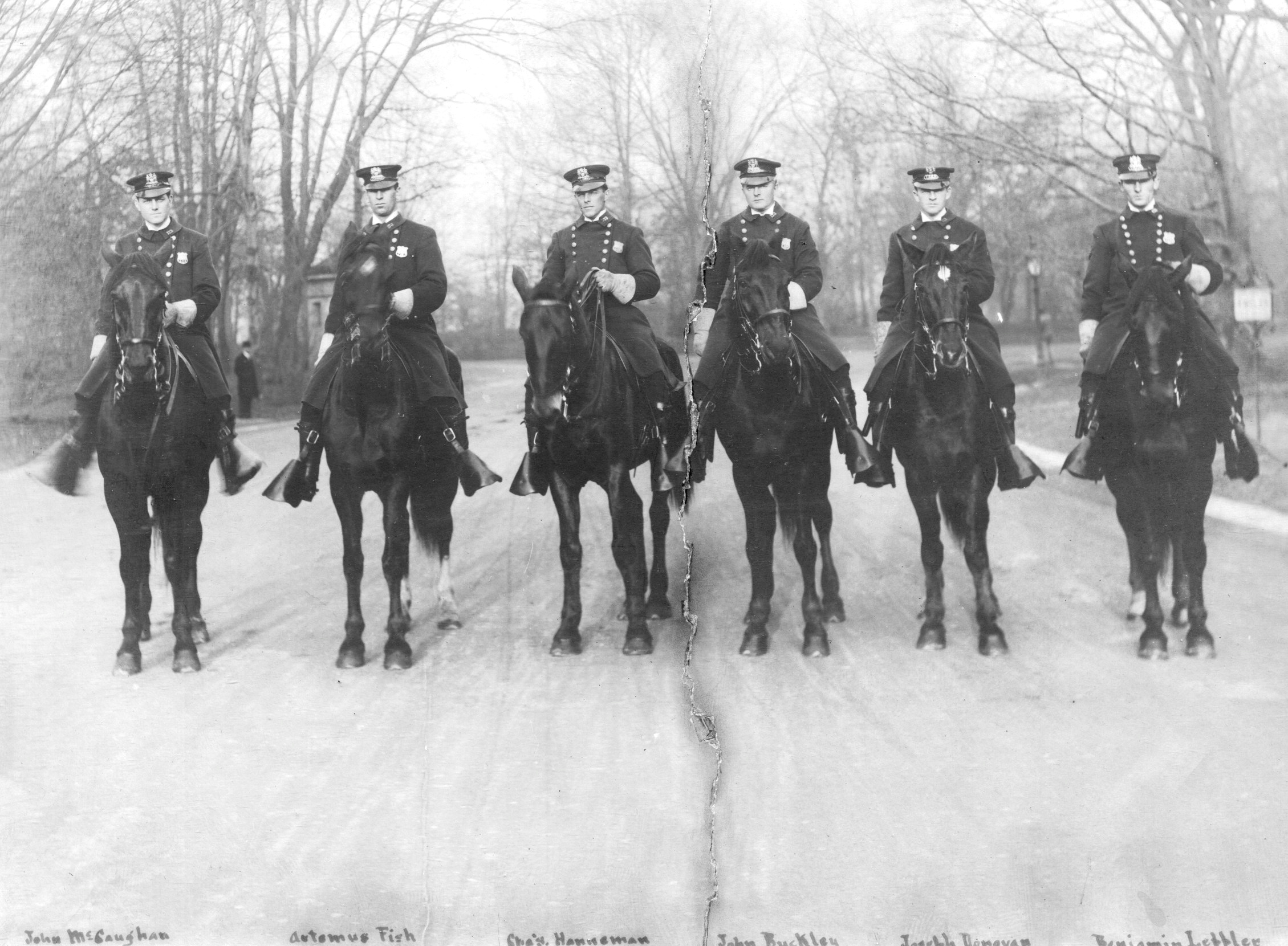

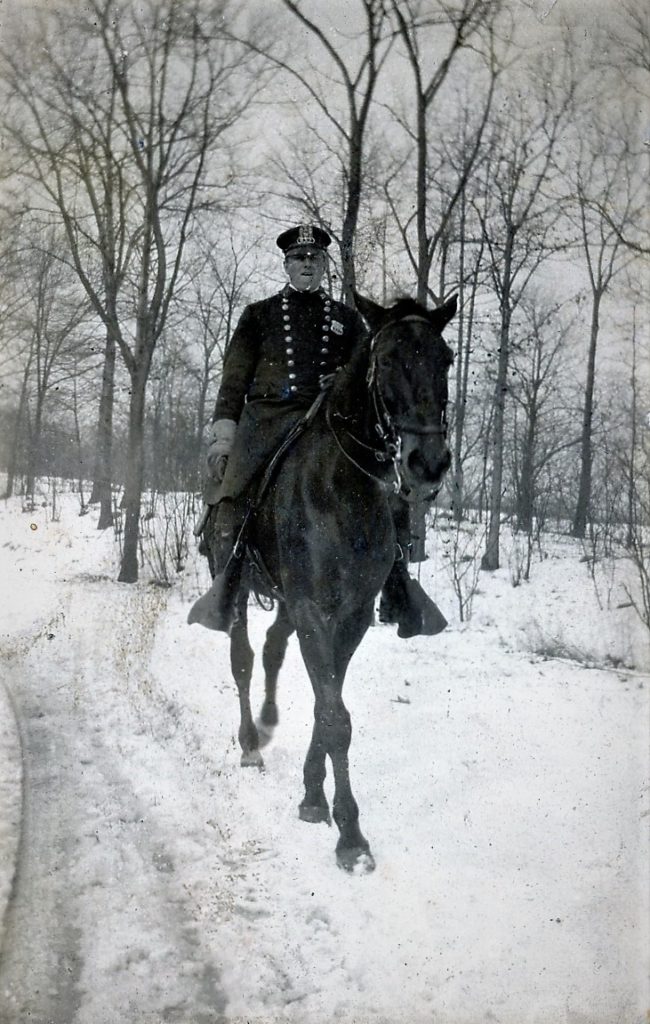

Benjamin’s first instinct was to determine if Tom was still alive, but the dogs would not allow it. Famished but faithful, the fox terriers nipped and barked to keep Benjamin away from their master. The janitor summoned the police from the Oak Street police station.

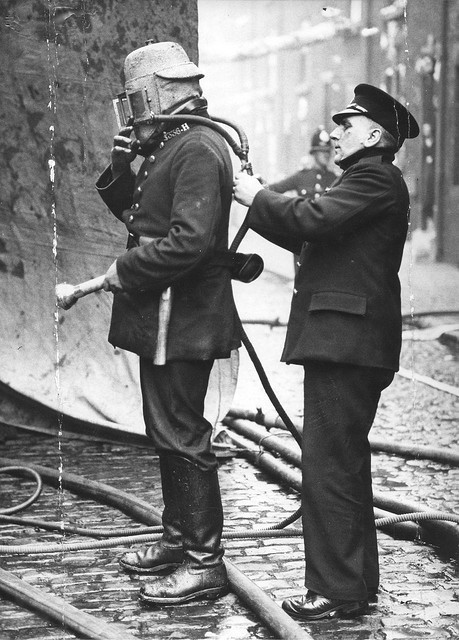

When the two patrolmen arrived, it took some effort to get the dogs under control. Despite their starving condition, the fox terriers gave it their best: One of the adult dogs even bit Patrolman Edward Kilgallen on the ankle before finally surrendering.

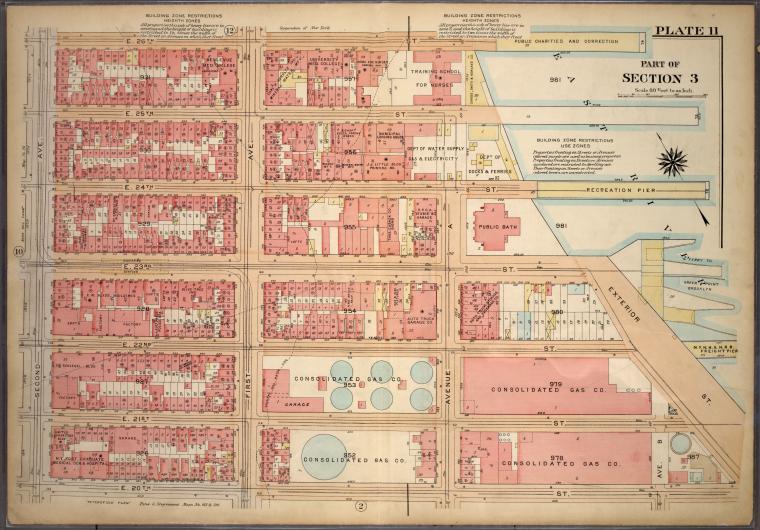

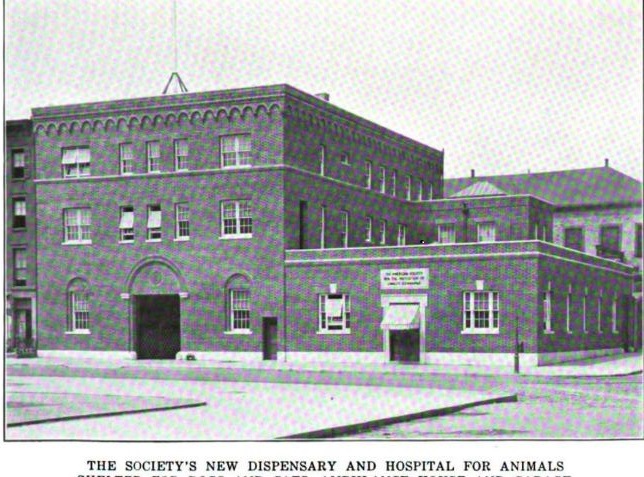

While Old Tom was taken to the morgue, his dogs were taken to the ASPCA hospital and shelter at Avenue A and 24th Street, directly across from the East 23rd Street Bathhouse. The fox terriers were given their own baths and fed, and assigned the following numbers: Dog 141,293; 141, 294; 141,295; and 141;296.

Guarded Dead Master, Dogs Face Execution

The day after Tom’s body was discovered in the cellar, The New York Times reported the story. Two days later, the paper said that the police were seeking homes for the faithful terriers “of undistinguished ancestry” to prevent their execution. The headline read:

Guarded Dead Master, Dogs Face Execution: If they don’t find homes soon, they’ll be executed by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

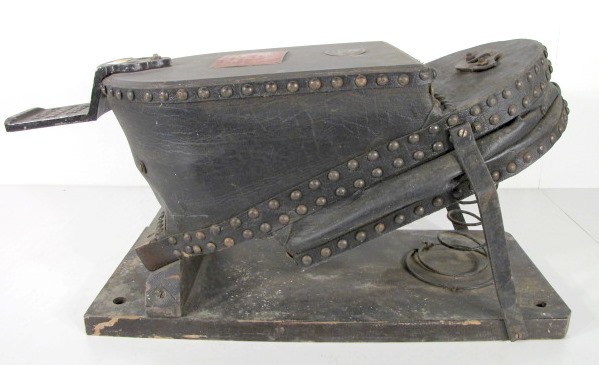

The calls came pouring in. Within two days, more than a dozen people had applied to adopt the homeless and master-less terriers. The dogs were thus saved from the “death chamber,” a small steel gas tank with glass observation windows where the animals were “humanely” asphyxiated (at one time, about 2,500 cats and dogs were euthanized every week in this gas tank).

Because one of the dogs had bitten a police officer, the New York City Health Department ruled that they first had to undergo ten days of quarantine at the shelter to observe for rabies. They also had to be officially released by the Public Administrator, since the dogs were a part, if not all, of Old Tom’s estate.

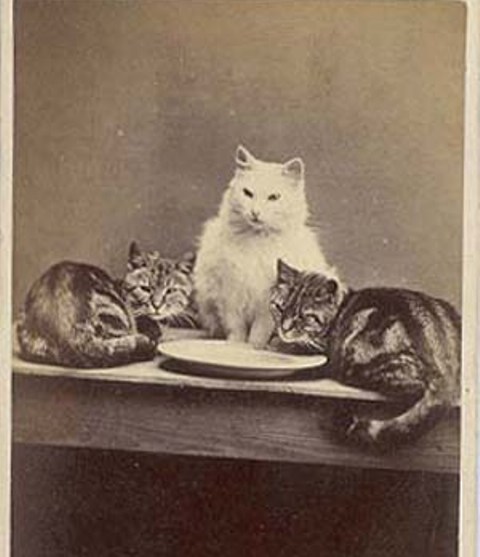

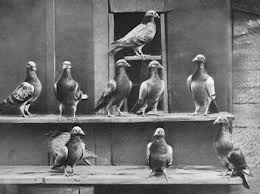

As a special treat for Thanksgiving Day, the ASPCA bestowed names on the fox terrier family: Spot One (the mom), Spot Two (the dad), Spot Three (the daughter), and Spot Four (the son). The terriers were henceforth known as the Spot Family. For Thanksgiving, the dogs also received boiled beef that was browned in a pan, which was ordered by the shelter’s veterinarian.

One week after the dogs arrived at the ASPCA, William E. Bevan, general manager of the society, told the press that their ribs were no longer protruding and their fur had taken on a healthy sheen. He said they were also making friends with the 130 other canines at the shelter, although Spot One and Spot Two did not seem to appreciate rearing their puppies in the same room as a man-biting police dog and a woman-biting Boston bull terrier.

Offers to adopt the dogs continued to come in (43 total, including several from New Jersey and one from West Virginia), but many of the prospective owners said they could take only one dog. The ASPCA wanted to keep the Spot Family together.

Then one day the society received a phone call and a signed petition from a home for blind women on Long Island, which wanted all four dogs to keep the women company. The society decided that the home for the blind would be the dogs’ new forever home.

Sadly, the night before the dogs were scheduled to go to Long Island, Spot Four passed away. The two pups were only about five weeks old, so the poor thing was apparently too young and weak to survive his ordeal.

On December 2, 1930, the three surviving members of the Spot family went to their new home on Long Island. On that very same day, Old Tom was sent to potter’s field.

A Brief History of New York’s Potter’s Field

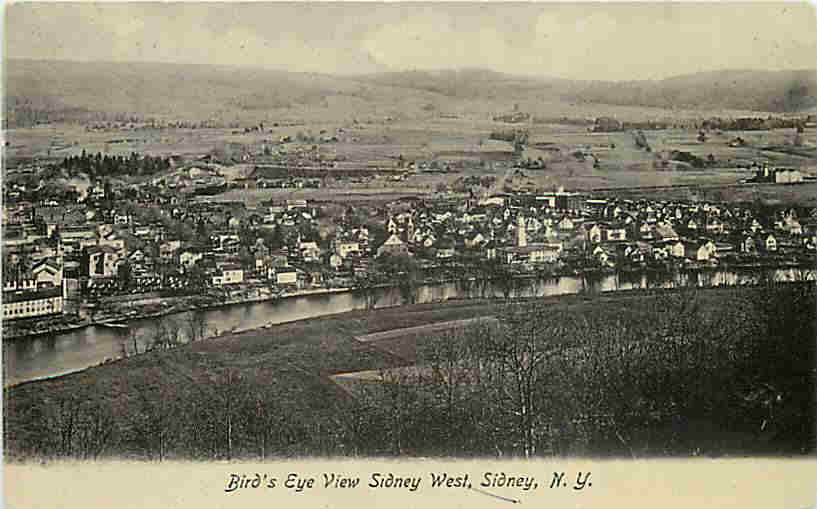

A century before unclaimed bodies were buried on Hart Island, the areas now known as Washington Square Park, Madison Square Park, and Bryant Park served as potter’s fields. Madison Square Park served as the first mass grave site from about 1794 until it was full in 1797.

The potter’s field was moved to Washington Square, but after the yellow fever epidemic of 1823, the city barred further burials downtown and routed new corpses north to what is today Bryant Park. When that area was chosen as the site of the Croton Distributing Reservoir (now the site of the New York Public Library) in 1840, the remains of about 100,000 paupers were transferred to Ward’s Island. On April 20, 1869, Louisa Van Slyke became the first person buried on Hart Island.

Today, inmates from the prison on Rikers Island, New York City’s main prison complex, receive the dead, which are then shipped to Hart Island on a ferry run by the Department of Corrections. The deceased’s name (if known) and identification number are carved into the coffin, and a packet with other identifying information is attached to the coffin. John and Jane Does constitute one-tenth of all burials, and only about one hundred bodies are identified by relatives or friends each year.

The cemetery on Hart Island is dotted with white markers, each denoting a mass burial of 150 bodies laid out in two rows, three coffins deep. None of the dead have personal grave markers, but there are two large monuments dedicated to all who are laid to rest there.

What happened to the ASPCA dispensary and ambulance house?

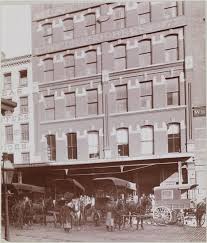

The ASPCA dispensary and ambulance house, where the Spot Family awaited their new home, opened in August 1912 at the southwest corner of Avenue A (today’s Asser Levy Place) and 24th Street. The complex featured a one-story structure with kennels for homeless, abandoned, and stray animals, as well as a lethal chamber where they were “humanely” euthanized via a gas chamber. An adjoining three-story structure contained the ambulance house on the ground floor and numerous rooms on the second floor, including a waiting room, examining rooms and operating rooms for small animals, separate wards for dogs and cats, an isolation ward, kitchen, and storeroom.

The second floor also had stalls and operating rooms for horses, which were transported from the ground floor via a sling and an electric trolley. The third floor had isolation stalls for the horses, a janitor’s living quarters, a bedroom for the resident vet, a hay and feed loft, and a repair shop. On the roof of the shelter was an exercise runway for the dogs.

Following World War II, the federal government, under the direction of President Harry Truman, ordered the ASPCA to vacate the premises to make room for a new six-acre Veterans Administration (VA) hospital. The ASPCA moved out in August 1950, and relocated to York Avenue at 92nd Street. Today, the handicap parking lot of the VA NY Harbor Healthcare Manhattan Campus occupies the site of the old dispensary and shelter.

What happened to Oak Street and the Fourth Precinct Police Station?

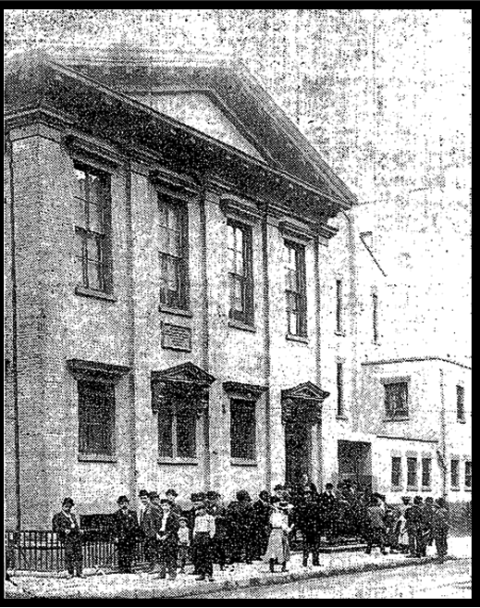

Oak Street was a short street in the Lower East Side that ran parallel to Madison Street between Pearl and Catherine Streets. In 1870, the Fourth Precinct station house, which was one of the oldest in New York, was replaced by a new brick station house at 9–11 Oak Street, near Roosevelt Street. The complex included a four-story main building and two-story rear building for housing prisoners and vagrants.

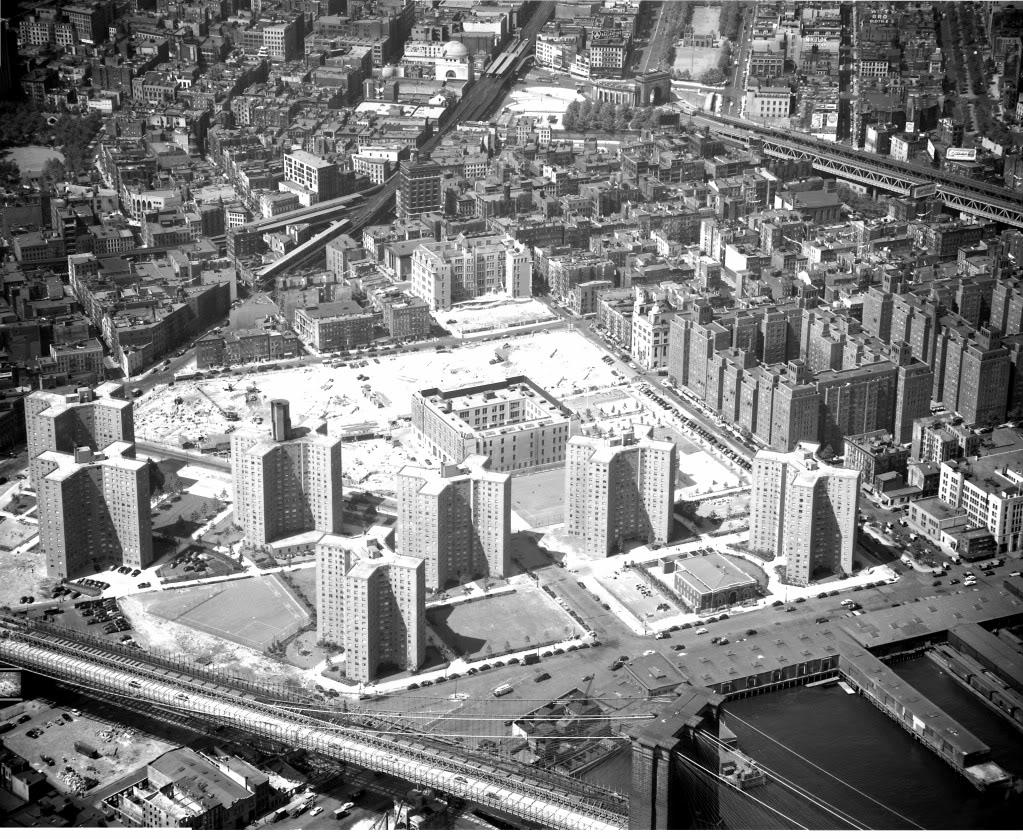

In 1947, the buildings on Oak, Roosevelt, and several other old streets were razed for construction of the Governor Alfred E. Smith Houses, Alfred E. Smith Memorial Park, and Public School 114. Ground was broken for construction of the public housing complex in 1949, and the project was completed on April 1, 1953. Where the old station house once stood is now occupied by the northwest portion of this complex and PS 126 Jacob August Riis School (now Manhattan Academy of Technology).