Part I of a Parkville Precinct Puppy Tale

In 1907 the Police Department of the City of New York, under the command of Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham, sent Inspector George R. Wakefield to Paris and Ghent, Belgium, to look into acquiring some police dogs. Police dogs had been gaining popularity in Europe since their first introduction in Ghent in the late 1800s, and many periodicals were touting the benefits of adding dogs to police forces in rural areas.

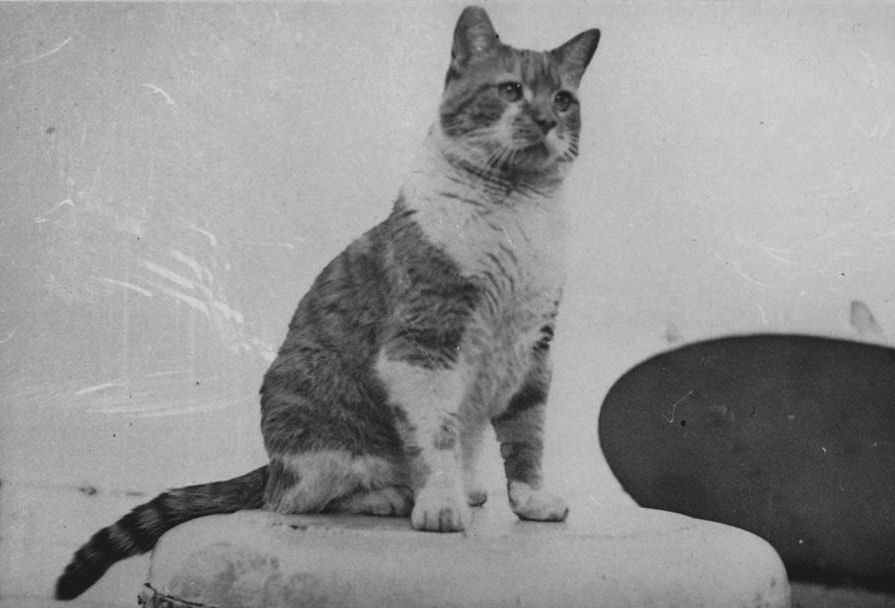

Inspector Wakefield was most impressed with the dogs in Ghent, who were trained to trust only men in uniform – and to distrust any man lying down or crouching. In order to test them out, he donned a Ghent patrol uniform and walked the streets of the city at night with a dog. Wakefield brought back five young Belgian sheepdogs, each about a year old. The five pups — Jim, Nogi, Lady, Donna, and Max — made up the first genuine canine squad in New York City and, in fact, all of America.*

The total cost of the trip and acquisition was $364.84, which included $50 for all five dogs; $132 for fare to and from Belgium; $48 for board; $3 for cabs; $25.60 for incidental expenses incurred while looking for the dogs; $6.60 for three crates; $50 for freight; $10 for duty; and $2.65 for a book on training police dogs. Herman A. Metz, Controller of the City of New York, said Wakefield’s trip was the cheapest of its kind on record. Even the customs inspectors questioned the paperwork, believing the dogs should have cost $1,000 each.

“Men in uniforms are friends – all others are possible enemies”

Upon arriving in New York, the dogs were placed in the department’s kennels near Fort Washington Point, at the intersection of Riverside Drive and Depot Lane (aka, Road to Depot; today’s W. 177th Street). Under Inspector Wakefield’s direction, the five canines received about three months of special training.

According to Walter A. Dyer, author of A Police Dog in America (1915), the dogs were trained to obey fundamental commands and to recognize men in uniforms as friends (and all others as possible enemies), to answer at once to the police whistle or the rap of the stick, to hurl themselves upon someone attacking a policeman, to pursue and throw a fleeing criminal, to search around buildings at night, and to signal bark in of the presence of persons lurking in the shadows.

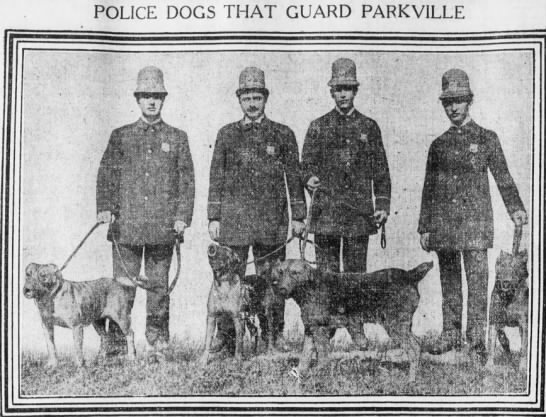

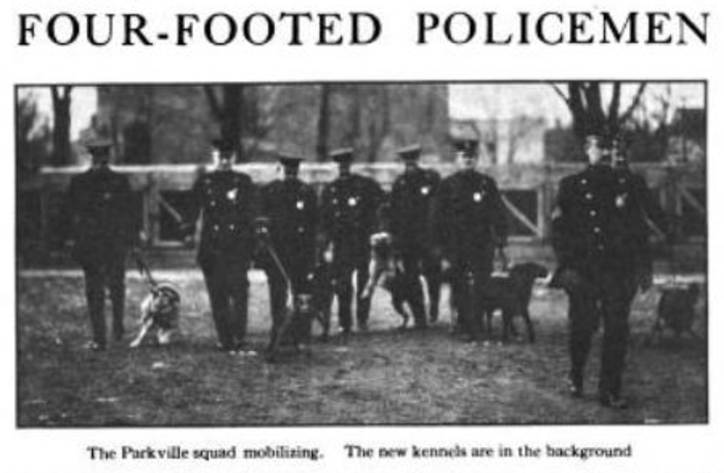

The police pups arrive in Parkville

Following their intense training, the five canines were declared fit for service in January 1908 and placed in the 72nd Precinct in Parkville, Brooklyn. The residential village on the west side of Flatbush had been the scene of numerous night burglaries; hence, the Police Department chose Parkville to experiment with the new canine patrol. One patrolman was placed in charge of the care and feeding of the dogs, and each dog was assigned to one of five policemen who were chosen because of their love for dogs and their interest in the work.

16 outdoor kennels with runways were available during good weather.

The two-legged and four-legged partners teamed up for duty every nght from 11 p.m. to 6 a.m. The men would keep the dogs on leash going to and from their posts and then release the dogs once on patrol so they could check out the back of each property for marauders or thieves. The dogs often put in 25 or 30 miles during each seven-hour shift as they ran across fields and investigated the countryside of Parkville, Brooklyn.

Max to the rescue

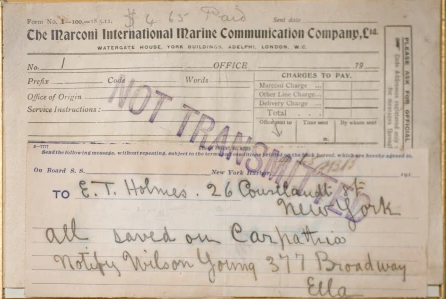

During their first few days at the Parkville police station, the police dogs were kept on a leash at all times. On January 29, 1908, the leashes were put away on post and the dogs went to work. Thanks to this freedom, Max was able to make an incredible rescue and save a man he found freezing in the snow.

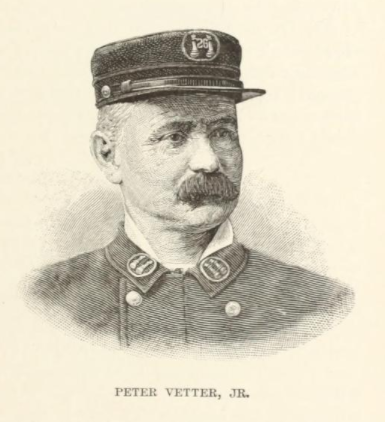

At about 8 p.m. that night, the officers heard a scratching on the station house door. Max bounded inside, ran past several plain-clothed officers, and headed to Lt. Frank Kelly. He began dragging Kelly by his coat to the door, which caught the attention of Acting Captain William H. Funston.

The captain, who was in plain clothes, tried to coax the dog outside, but Max refused to follow – the captain could have been an enemy, after all. Max did agree to leave with Officer Scally, who was in uniform, and once he was assured the men were following him, he bounded out of the station and started to run.

Max led the officers from the station at Ocean Parkway near Foster Avenue to a vacant lot at 37th Street and 15th Avenue, nearly a mile away. He waited for the officers to catch up, and then led them behind a snow bank, where they found a man half frozen and unconscious. The man was taken to the station in a patrol wagon and received medical treatment. He said he was Edward Connolly, a cook on the steamboat Robert M. Doyle, and had been drinking before he went into the lot. Mr. Connolly was locked up and charged with intoxication.

Following the rescue, Lt.Wakefield told the press, “Max was the most intelligent dog of the bunch.”

Now here’s the question: Was Max really smart enough to lead the officers to Edward Connolly because he knew the man was in trouble, or did he think the man was someone bad because he was lying down? Stay tuned for my next amazing rescue tale starring Max — it may lead you to believe that Max was very intuitive.

From Greenfield to Parkville

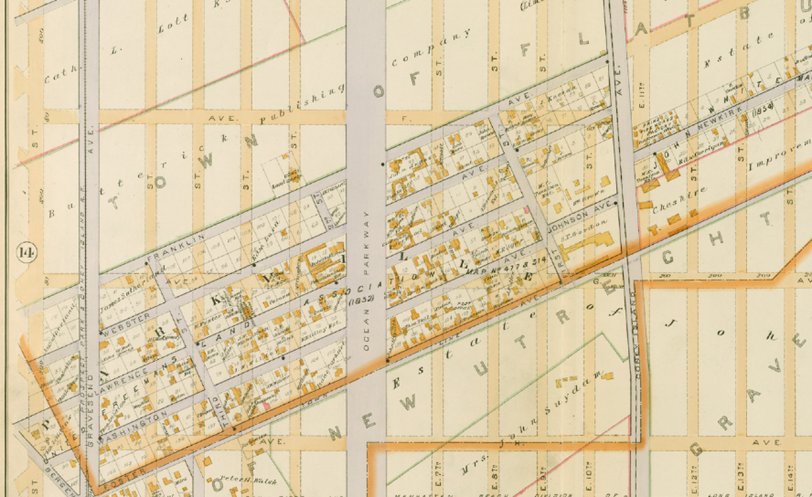

From 1851 to 1852, the United Freeman’s Association purchased the John Ditmas and Johnson Tredwell family farms in the Greenfield section of Flatbush – a total of 114 acres – for about $57,000. In 1853 the Association laid out a system of streets that intersect Brooklyn’s north-south street grid diagonally (which are still present today), making the village, with its detached frame houses, one of the most attractive suburbs in Brooklyn.

In 1871 the name of the village changed to Parkville; completion of the northern section of Ocean Parkway in 1875 further spurred the neighborhood’s development.

Rural Parkville goes urban

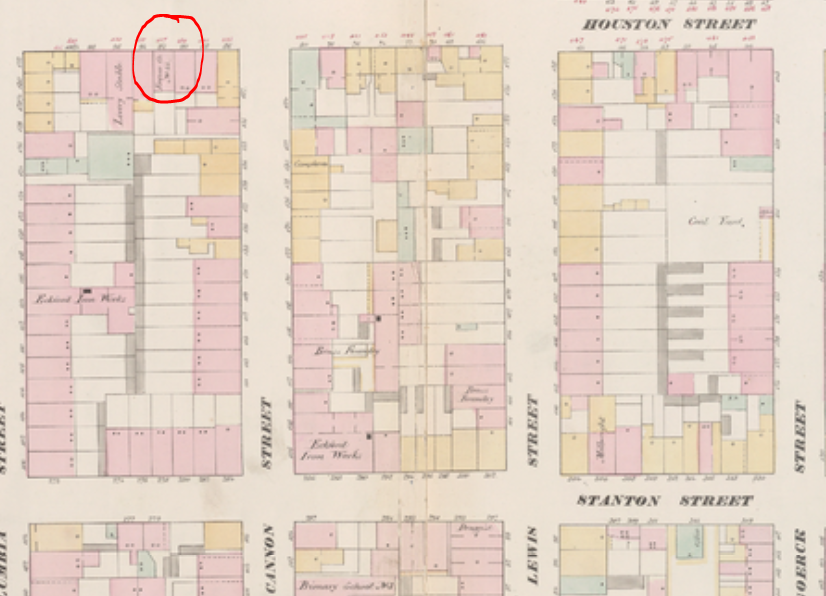

Although there were numerous vacant lots at the intersection of 37th Street and 15th Avenue around the turn of the 20th century – including a few large lots next to what was then the Flatbush Corporation Building — a 1917 map shows that much of the area was fully developed by this time. The fields, farms, dirt paths, and frame homes and stables belonging to prominent land owners like R. Hegeman, Colonel Joseph G. Story, and George Martense – all of which appear on an 1890 map of the same intersection – had been replaced by brick, concrete, asphalt, and industry.

If you enjoyed this story, you may want to read about the Parkville Police Dogs’ Debut at Madison Square Garden in Part II of the Parkville Precinct Puppy Tales or about the additional police dogs obtained following a jewel heist in 1908.

*Except for tentative experiments made in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., New Haven, Conn., and Glen Ridge, N.J., New York was the first American municipality that made a fair test of a dog squad as a part of its police force.