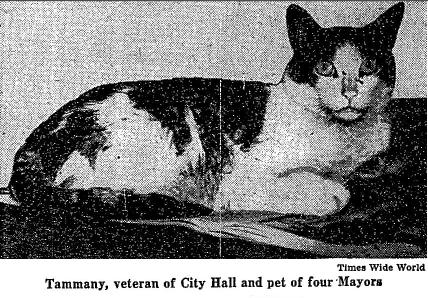

I once wrote about Old Tom, who was a very popular mascot of New York’s City Hall in the early 1900s. Although several other cats took over Tom’s place at City Hall after he died, none of these felines were as popular as Tammany, who occupied City Hall during the administrations of Mayor Jimmy Walker and Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in the 1930s.

Tammany’s life of luxury as the City Hall cat began sometime around 1930, when New York Mayor James J. Walker found the cat on the Lower East Side. Mayor Walker named the cat Tammany and brought him to City Hall to help get rid of rats in the building. Tammany was apparently quite the charmer, because during the remainder of Mayor Walker’s reign, his rat diet was supplemented by calves’ livers that came out of the city budget.

Tammany took his job as the City Hall feline boss very seriously. As the New York Sun reported, he was “a bold, swashbuckling lad” and no rat was too big to escape his claws. In addition to rat-catching, Tammany would make the rounds of the building, checking in on a Board of Estimate meeting or a Council session, or dropping by to visit the mayor, whose door was always open for him.

Between visits he’d stretch out in the main corridor and check out the visitors. If the visitor was feline, he’d chase the cat out of the building without mercy. When his work was done, he enjoyed sleeping in his dank cellar retreat.

Tammany was also a great friend of the City Hall reporters – well, he didn’t really like them, but he spent a lot of time in Room 9, the reporters’ room, sleeping on their desks.

The reporters loved to pose Tammany for pictures, but he didn’t love the publicity. Sometimes after being photographed sitting on a reporter’s desk, stalking the halls of City Hall, or looking out the window, he’d spend the rest of the day sulking in the cellar.

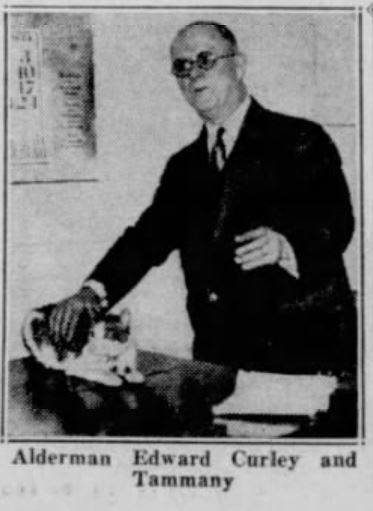

The men on the Board of Aldermen also enjoyed Tammany’s company, especially if he did something to break up a meeting. One day in the winter of 1934, the cat created quite a stir when he stared down Alderman Edward Curley of Bronx, who was angrily denouncing Mayor LaGuardia.

While Curley was calling the mayor “a self-declared monarch of all his surveys,” Tammany woke up from his nap on a chair near the dais and began nudging the alderman and staring into his face.

As the other alderman’s laughter drowned out Curley’s oration, Aldermanic President Bernard S. Deutsch said, “I think the sergeant-at-arms had better escort the silent member to the back of the room.”

The aldermen responded, “No, no, let him alone!” Alderman Walter R. Hart of Brooklyn then leapt to his feet and said, “I move that the privileges of the floor be extended to the City Hall cat.”

“City Hall Cat’s Job Safe Under LaGuardia”

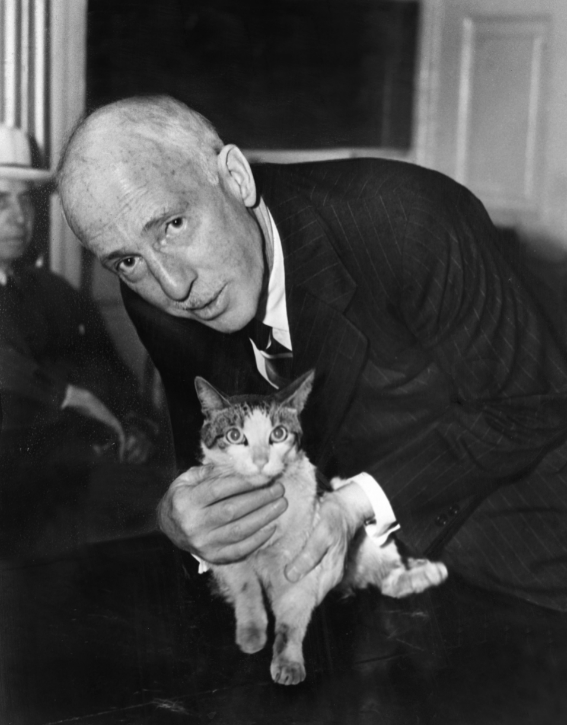

Although Tammany’s job was quite secure under Mayor Walker, his fate was questioned by the New York press when Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia took office in 1934. After all, the anti-Tammany “reform” mayor was not a member of the Democratic party – he ran on the Republican-Fusion ticket.

Right from day one, Mayor LaGuardia reorganized the city cabinet with non-partisan officials in his quest to develop a clean and honest city government. As Tammany watched many of his old friends leave City Hall, perhaps he also pondered his own fate under Mayor LaGuardia.

Mayor LaGuardia apparently had no intention of evicting Tammany from City Hall. On January 6, 1934, the headline on the front page of the New York Sun said, “City Hall Cat’s Job Safe Under LaGuardia.” A photo of the mayor with the cat in the foreground accompanied the article (unfortunately, the photo is too dark to post). Shortly thereafter, Tammany was wearing a collar that said “City Hall Custodian” in case he should get lost.

Although the new mayor had no intention of sending Tammany back to the streets of the Lower East Side, life did get a little more challenging for the cat under the “Fusion frugality.”

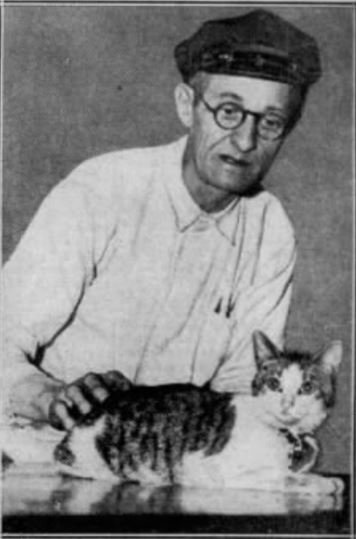

No longer were his meals a line item on the city budget; now he had to rely on Tom Halton, a watchman at City Hall, and John Helmuth, night patrolman, who paid for Tammany’s evening meal out of their own pockets. He also had to deal with a cat named Fusion who tried to move in on his territory. This silent battle for control lasted for three weeks, until Fusion disappeared one night during a storm. Hmmm….

The Deputy Mayor Comes to Tammany’s Rescue

Tammany also had to contend with Commissioner Edward M. Markham of the Department of Public Buildings, who, according to rumors, was conspiring with the ASPCA to evict the cat from City Hall. Luckily, he had an ally in Deputy Mayor Henry Hastings Curran, who declared City Hall was under siege when he found out about the plan.

On June 13, 1938, Curran wrote a letter to Markham in which he pleaded for clemency, noting Tammany was “the wisest and bravest of all cats.” Curran said the cat had 50,000 friends at City Hall who would fight for him if the ASPCA tried to take him away. “The carnage will be cheerful, instantaneous, and complete,” he wrote. “Let them come!”

The Tragic Death of the Boss Cat

On April 9, 1939, Tom Halton could not find Tammany when he went to feed him at 5 p.m. The next day around noon, the City Hall reporters spotted him in a telephone booth in their room. He had keeled over and was whimpering in pain.

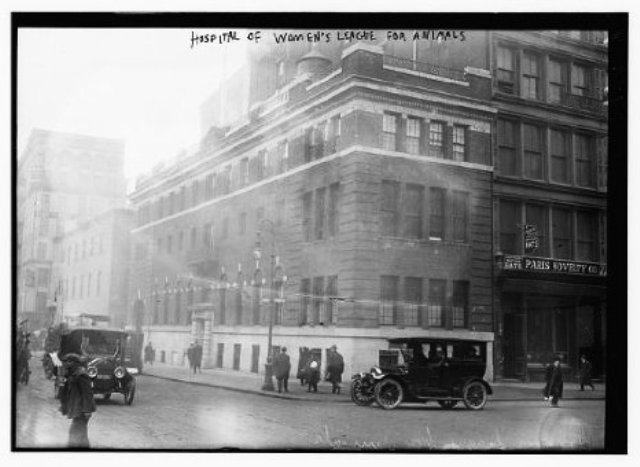

Deputy Mayor Curran immediately called the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals to let the vet know he was coming with the cat. Then he commandeered a car belonging to Council President Newbold Morris, and, escorted by two policemen, rushed Tammany to the animal hospital on Lafayette Street.

There, Dr. James R. Kinney gave him a fluoroscopic exam, which showed the cat was suffering from uremic poisoning and stones in the bladder. Dr. Kinney and his assistants sat up with the cat all night, but at 7:30 a.m. the next day, Tammany passed away. City Hall workers and reporters were notified of his death as they came to work. More than 200 calls came into City Hall that day from people who wanted to give Curran and LaGuardia their condolences.

James Speyer, the husband of the late Ellin Prince Speyer, offered to bury Tammany in a little pet cemetery at Waldheim, his large country estate at Scarborough-on-Hudson. The inscription on the grave read, “Tammany – In Fond Memory of Our Cat – Room 9, City Hall.”

Some pretty lucky “political” cats in the 1900’s Wonder of there are any such felines today.,

[…] May 3, 1939, one month after popular City Hall cat Tammany died at the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital, an 11-month-old multicolored female cat from Woodside, […]