The first cat to cross over the Brooklyn Bridge was a gray cat named Ned. This vintage kitty is not Ned, but isn’t he cute?

In 1866, the New York State Legislature passed legislation authorizing the construction of an East River bridge to connect Manhattan and Brooklyn. A year later, the New York Bridge Company was incorporated and John A. Roebling, who presented a design for a 1,600-foot bridge, was appointed chief engineer for the Brooklyn Bridge.

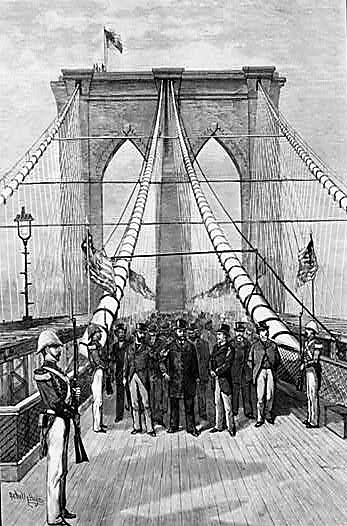

Following a series of major construction milestones and setbacks—including John Roebling’s death, son Washington Roebling’s injuries from “caisson disease” (decompression sickness), and William “Boss” Tweed’s arrest for stealing public funds—the new Brooklyn Bridge (then called the East River Bridge) opened to traffic 16 years later on May 24, 1883.

On that day, Washington Roebling’s wife, Emily Warren Roebling—who had directed the bridge project via written and verbal instructions from her bed-ridden husband—was the first person to travel across the completed Brooklyn Bridge by horse-drawn carriage.

The first two members of the general public to cross the bridge on foot and pay the penny toll were a news reporter and Marty Keese, the long-time custodian of New York City Hall, who raced each other across the bridge when it opened to the public at midnight.

Emily Warren Roebling reportedly crossed the Brooklyn Bridge with a rooster at her side to symbolize victory. According to a news article about her death in 1903, this rooster was stuffed and put on prominent display at the Roebling Museum.

All of this information (save for the details about the reporter and Marty Keese) is covered extensively in books, documentaries, public reports, and historical websites.

The story of P.T. Barnum’s proposal to “test out the bridge” by walking a troupe of elephants across the span right after the bridge opened is also fairly well documented.

What most people don’t know, however, is that a month before the bridge opened to the public, a Brooklyn stray cat named Ned crossed the bridge from Brooklyn to Manhattan. In fact, had I not come across the small, one-paragraph article about Ned buried in the New York Times by chance, I never would have known this feline fact either.

According to the article, C.W. McAuliffe, a New York saloon keeper and renowned Republican supporter, had requested the first cat to be persuaded to cross the new Brooklyn Bridge. Alderman James J. Mooney went in search among the stray Brooklyn cats, and found a grey cat “that was inclined to see the world.”

Mooney placed the cat in a basket and presented him to Charles Cyril Martin, the chief engineer and superintendent of the Brooklyn Bridge. Martin handed the basket to a bridge worker, who took the cat to the center of the bridge.

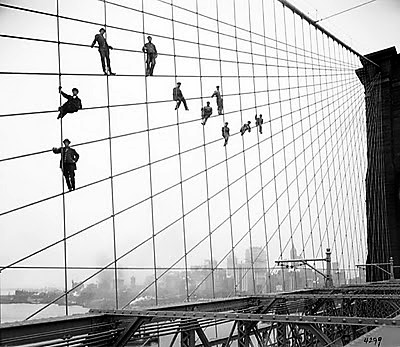

The Brooklyn Bridge painters must have had cat-like skills in order to cling to and balance on the steel cables.

When the cat-bearer reached the center of the structure, he released the cat. The cat, who was not yet named, followed the worker toward Manhattan until they reached the end of the bridge. He was then placed back in the basket and delivered to McAuliffe at his saloon in Harmony Hall at 17 Centre Street.

President Chester A. Arthur, who presided over the dedication ceremony for the new Brooklyn Bridge, crossed over the bridge with New York Mayor Franklin Edson and other dignitaries. They were greeted by Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low on the other side. I doubt any of them knew that a cat had crossed before them.

There at the saloon, he was christened “Ned of the bridge” and presented with a new collar bearing his name. (I guess McAuliffe was counting on the cat being male, since he must have premade the collar for this occasion.)

I don’t know what happened to Ned after this day, but the Republican politicians in attendance were reportedly very merry over the event (perhaps they had too much gin?). I certainly hope that Ned was allowed to stay on at Harmony Hall as the saloon’s mascot cat.

A History of Harmony Hall at 17 Centre Street

Harmony Hall, a three-story brick structure on the northwest corner of Centre and Chambers Streets in downtown Manhattan, dates back to about 1849, when it was a meeting place kept by an Englishman named John Whittaker. It was later called Park House, which was run by Abraham Sickles. Park House had hotel accommodations for about 20 guests and a barroom on the ground floor.

During the Civil War years, 17 Centre Street served as a pseudo headquarters for the 82nd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment. When this story takes place, the barroom was run by C.W. McAuliffe, who perhaps inherited the business from his brother Henry, who reportedly died in his residence at Harmony Hall in 1881.

In 1888, Thomas P. “Fatty” Walsh, the former Tammany Hall warden of the Tombs prison who was forced to resign on extortion and other charges, opened his third drinking place at 17 Centre Street. (Walsh had previously operated saloons at 149 Fulton Street and 7 Mulberry Street.) Two years later, Walsh surrendered the business to Assemblyman Timothy Daniel “Dry Dollar” Sullivan (aka Big Tim Sullivan), a prominent Tammany Hall leader. Walsh then reportedly took a low-paying job as a watchman at Pier A on the Hudson River.

Sullivan called his saloon the Wigwam, and for several years it served as the headquarters for the Sullivan Democracy of the Second Assembly District (also known as the Tammany Naturalization Bureau). In 1892, he sold the business to Florence Jupiter “Big Florrie” Sullivan, a very distant cousin.

Sometime around 1901, the old Harmony Hall was razed to make way for the grandiose Surrogate’s Courthouse, also known as the Hall of Records.

This photo of Centre Street between Chambers Street and Reade Street was taken in 1901. The photo shows the partially constructed Hall of Records (white building on the right–only the ground floor has been completed at this point) and a frame work shed used by the subway construction workers. A low structure on the southwest corner that was occupied by Engine Company No. 7 and Hook and Ladder No. 1 is also just visible on the far left. The plain brick building behind the Hall of Records could possibly be 17 Centre Street, just before it was torn down. The old City Court and the Home Life Insurance Company Building are behind this. New York Public Library Digital Collections

The New Hall of Records

Prior to 1831, public records were housed in City Hall. In 1830, the Common Council authorized the conversion of the old eighteenth-century jail in City Hall Park to fireproof offices for a Hall of Records. The council also appropriated funds to make extensive exterior alterations to the old jail so that it would complement the City Hall building.

In 1870, another floor was added to the building to accommodate the growing need for more space to store public records. They also added a fireproof roof.

In 1888, the city formed the Sinking Fund Commission to erect a new Hall of Records in the vicinity of the New York County Courthouse. The law authorizing its construction was amended in 1890 to accommodate other city offices, and again in 1892 to allow the building to be constructed in City Hall Park.

At this time, the city began making plans to raze the old City Hall building. There was even a national competition that brought in more than 130 design entries for the new building.

New Yorkers were completely against the plan to destroy the building–and the public outcry was heard loud and clear. Instead of razing it, the Board of Alderman authorized a project to clean and renovate City Hall in 1895.

Here is the former Hall of Records in the old jail building in 1890. Notice the odd additional floor that was added above the former roof line to accommodate the city’s records in 1870. NYPL digital collections.

In the last year of the nineteenth century, architect John R. Thomas was commissioned to build a new Hall of Records building on the northwest corner of Centre and Chambers Streets. Thomas based the design on his award-winning plan for the new City Hall building that was never constructed. The eight-story Beaux Arts building was constructed between 1899 and 1907.

In 1962, the name of the Hall of Records was officially changed to Surrogate’s Courthouse. Both the exterior and interior of the building are New York City Landmarks. The building is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

In this 1908 photo, the Hall of Records building at Chambers and Centre Streets is completed. Across the street, the vacant lot is being prepared for the new Municipal Building (now called the David N. Dinkins Manhattan Municipal Building), which was designed by McKim, Mead and White and constructed between 1909 and 1914. NYPL Digital Collections

Here’s to Ned o’ the Bridge! Great article!