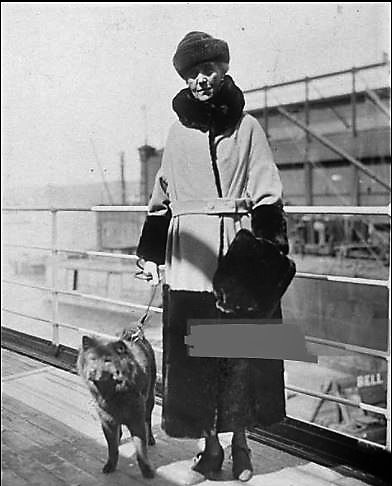

Mrs. Anne Harriman Sands Rutherfurd Vanderbilt — the second Mrs. W.K. Vanderbilt — poses on board a ship with a dog in 1930. (Perhaps she went back to Belgium to get another police dog for the Watsons following Billy’s death in Harlem in 1929…)

In 1921, Mrs. William Kissam Vanderbilt purchased a thoroughbred German police dog while traveling in Belgium. She presented the dog to Mr. and Mrs. S.W. Watson of Harlem, who at one time had been paid servants in the Vanderbilt mansion.

German police dogs from Ghent, Belgium, were quite popular with dog lovers and breeders in New York City during the early decades of the twentieth century. Perhaps it was because the German police dogs that first joined the New York City Police Department in 1908 often made the headlines for their heroic deeds.

Or maybe it was due to the prolific newspaper advertisements touting the benefits of “police dogs” for wealthy city dwellers who needed a special dog to guard their jewels and their homes.

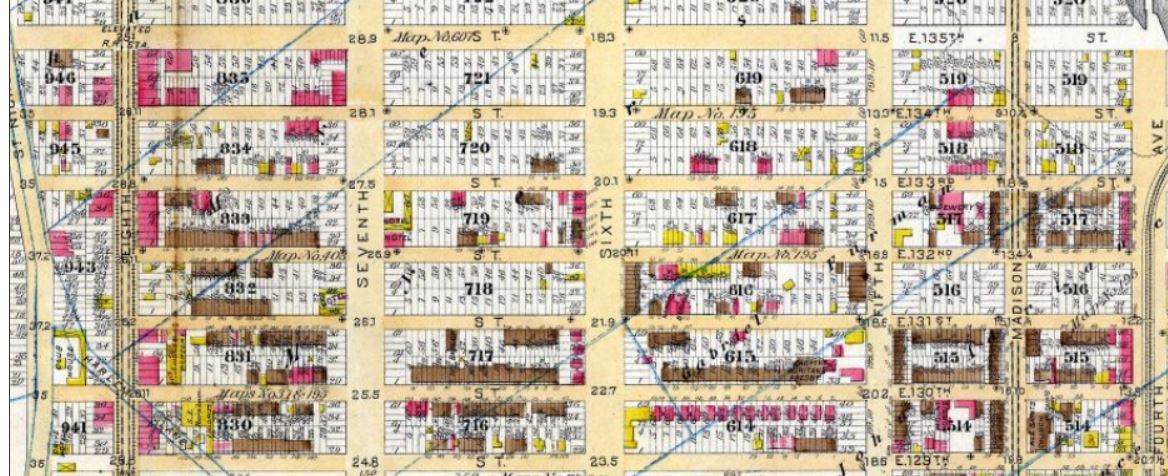

For eight years, Mr. and Mrs Watson lived with their dog, Billy, in their Harlem apartment at 2817 Seventh Avenue, between West 129th and 130th Streets.

I don’t know anything about Billy’s life in Harlem, but I do trust that the Watsons treated him well. Several weeks before his passing on July 17, 1929, Billy became very ill. Desperate to save his life, the Watsons employed four veterinary specialists to help save the dog they loved so much.

Mother Nature prevailed, and Billy left this world with his caring pet parents and at least one canine sibling at his side.

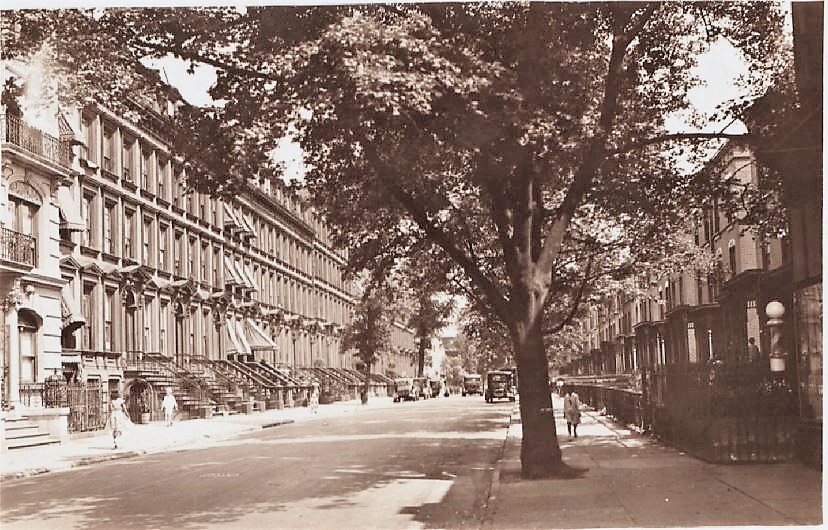

The Watsons lived with Billy and at least one other police dog at 2187 Seventh Avenue (seen at right in this undated photo), a brick building called “The Savoy,” constructed sometime between 1885 and 1891. The building was originally owned by Lawrence Delmour, followed by Harry Goodstein, Mrs. Annie Herman, and Philip F.O. Grant. New York Public Library Digital Collections

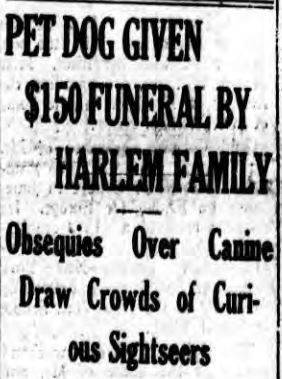

The funeral for the Watson’s German police dog made the headlines.

On July 19, the Watsons placed Billy’s body in a casket and brought him to the Louise B. Hart Funeral Chapel at 67 West 130th Street, near Lenox Avenue. The funeral home had been established only a few years earlier in 1925 by funeral director and embalmer Louise Hart, a native of Savannah, Georgia. Louise’s husband, William, was a barber who conducted his business in the same building until his death in 1937.

According to the New York Age newspaper, Billy’s service was “one of the strangest funerals ever seen in Harlem.” The brief service, which included an organ recital and a reading of the scriptures, was attended to only by the Watsons and their other German police dog.

A large number of curious spectators visited the chapel to view the dog’s body while it lay in state from that Wednesday evening until Friday afternoon. The Watsons buried their beloved dog Billy at the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery in Westchester County.

The Louise B. Hart Funeral Home was located at 67 West 130th Street, in a four-story, brick-with-brownstone circa 1910 building (pictured here on the far left) that Louise and her husband, William W. Hart, purchased from Blanche Waters in 1920. After daughter Lucille M. Hart joined the funeral business in 1944, the women moved to 1879 Amsterdam Avenue. Today there is a Louise B. Hart funeral home in Mount Vernon, New York. New York Public Library Digital Collections

Charles Henry Hall, a Harlem Pioneer

Both the Louise B. Hart funeral home and the Watson’s home were constructed on the former property of Charles Henry Hall, a wealthy lawyer, merchant, and land speculator who took a chance on Harlem that paid off rather well — well, at least initially — during the great railroad days in the early 1800s.

The funeral home was located on what had previously been the farm of Richard Harrison, and the Watson residence was on the old farm of Peter Myers. Both of these men, along with neighboring land owners including Arent Bussing, John Adriance and Benjamin J. Benson, had sold their large, diagonal, colonial-era holdings to Charles Hall between 1823 and 1825. Charles added these holdings to the adjoining 40-acre farm and homestead that he had purchased from Gabriel Furman in 1821 (for which he reportedly paid $13,000).

All told, Charles Henry Hall owned about 200 acres of land between about 126th and 132nd Streets, bounded by Third Avenue and the Harlem River on the east and the old Harlem Lane and Eighth Avenue on the west. The property was described in The New York Sun in 1885 as a beautiful tract with natural shrubbery, large forest trees, grassy lawns, and gently sloping hills.

Charles Henry Hall was a descendant of John Hall, who came to America by way of Coventry, England, in 1630, and settled in Charlestown, the capital of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (now part of Boston). John and his wife, Bertha Larned Hall, moved to Cape Cod and had twelve sons. Yikes.

Fast-forward about 120 years to January 20, 1754, the day an esteemed medical doctor by the name of Dr. Jonathan Hall was born in Sutton, Massachusetts. Jonathan settled in Pomfret, Connecticut, where he married Bathsheba Mumford of Newport, Rhode Island. Jonathan and Bathsheba had eleven children (yikes again). One of those children was Charles Henry Hall, born on December 26, 1781.

As a young man, Charles worked as a book-keeper (and was later a made a partner) for Thomas H. Smith & Co., tea merchants who made an enormous fortune in the China trade. He married Sarah Mullett on March 30, 1815, in Clapham, England.

Charles and Sarah had only three children: Charles Mullet (born 1817), Mary Jane (1819), and Eliza Ann (1822). However, the Hall family bred and raised many thoroughbred horses and thousands of Merino sheep on their land in Pomfret. (The sheep were reportedly the first Merino sheep in this country, and were so valuable they wore cloth coverings to keep dirt out of their wool.)

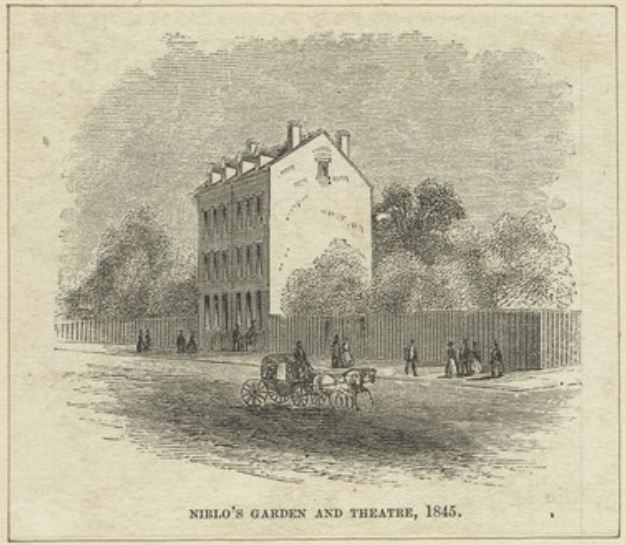

The Hall Home at 576 Broadway — Niblo’s Garden

When Charles and Sarah first came to New York City, they lived at 44 John Street in lower Manhattan. They later moved “far uptown” to a grand three-story house at 576 Broadway (constructed sometime after the War of 1812), located on an entire block bounded by Broadway, Prince, Crosby, and Houston Streets.

The property, which was directly across from the one-mile stone marker from City Hall, had once been part of the 160-acre Anthony Lispenard Bleecker farm. (A circus called the Stadium had reportedly occupied the northeastern corner of Prince Street and Broadway.) The farm was sold in lots to Jeremiah Van Rensselaer of Albany, who leased 576 Broadway to the Halls.

The rear of the large gabled-roofed, solid brick double mansion featured a spacious garden occupying half the block between Prince and Houston Streets. Along the rear of the garden, fronting Crosby Street, was what one reporter called “the most superb stables ever erected.” The stables were described as “a shingle palace, a marvelous structure of wood and glass, divided into chambers, the entrance to which bore the name of its equine tenants in huge golden letters.”

Sometime around 1828, William Niblo, the proprietor of the Bank Coffee House on Pine Street, acquired the Van Rensselaer property and converted the gardens into an open-air concert saloon. Surrounded by a plain board fence, Niblo’s Garden (originally called the Columbian Garden and Sans Souci Theatre) featured small alcoves with tables inside, numerous flower pots, and hundreds of colored-glass lanterns, which set the stage of a range of entertainment, including concerts, pyrotechnic displays, balloon ascents, and tight-rope walking.

William Niblo converted the former home, stables, and gardens of Charles Henry Hall into a restaurant, outdoor concert-hall, and, later, a large theater facing Broadway.

In later years, Niblo moved the stables to a more central part of the garden and had it altered into a theater that was partially open on the sides. The theater was destroyed by a fire on September 18, 1846; a replacement theater was also destroyed by fire in 1872. The third and final theater on the site was built by the department-store magnate A. T. Stewart. In 1895, it was demolished to make way for a large office structure erected by sugar-refining titan Henry O. Havemeyer, who also owned the adjacent Metropolitan Hotel.

Movin’ On Up

In the spring of 1829, Charles Henry Hall moved his family and his magnificent horses to the Gabriel Furman (aka Freeman) homestead near Fifth Avenue, between 131st and 133rd Streets. The old homestead was a large, square, two-story frame structure, with a wide piazza running entirely around it. The old home stood on a rocky mound surrounded by what were described as “charming fields and groves of trees.”

Nearby, was a fenced-in track for horse racing that ran from Fourth to Seventh Avenues on the south side of 125th Street.

It was here, at what became known as Hall’s mansion, in the heart of Harlem, that Charles entertained his friends in the style of a true gentleman of the old school.

The Gabriel Furman homestead included a large home and barn on 40 acres of land on the banks of the Harlem River surrounded by fields and groves of trees. If the house were still standing today, it would be behind present-day 32 West 132nd Street or 31 West 131st Street. From the John Randel Farm Maps, created from 1811-1820.

Charles renovated the building, enlarged it, and embellished it with broad carriage drives, serpentine paths, flowers, shrubbery, mulberry trees and other fruit trees (the orchard was near 135th Street and Fourth Avenue).

He also widened and deepened the existing natural hollows and filled them with rain water to create freshwater ponds and lakes. The ponds–including one near Fifth Avenue and 137th Street and another at Eighth Avenue and 125th Street–were stocked with goldfish, perch, and other fishes.

At one of the hollows near 135th Street, Charles installed a gate at the mouth of the inlet to prevent the return of the water to the Harlem River. The result was a large saltwater lake, which Hall improved with oyster and clam beds in addition to eels and saltwater fish.

This is not the farm of Charles Hall, but it was a neighboring farm at Seventh Avenue and 139th Street. It was called the great Pinkney estate, founded by Archibald Watt in the early 1800s and sold to his step-daughter, Mary G. Pinkney, following the Panic of 1837. The property and the family’s additional Harlem holdings were sold in 1911.

Charles welcomed the public to ride their carriages and sleighs on his carriage paths, row their boats and ice skate on his ponds, and stroll through his English gardens. He also donated some of his land at 127th Street between Lexington and Fourth Avenues (now Park Avenue) for St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, the first Episcopal parish in Harlem, which was organized in 1829. The church, a frame building on a stone basement, was completed on June 7, 1830.

In his spare time, Charles raised game cocks and fowls, and maintained a stable of 20 thoroughbreds. He also had the finest breed of short-horn cattle that grazed on his pasture lands.

This old frame home on Fifth Avenue and 130th Street, pictured here in 1895, was one of the buildings that had once been on Charles Hall’s property. Another house on the corner of Fifth and 132nd, which had once been occupied by Charles’ secretary, Charles J. Hubbs, was also still standing at least until 1888. NYPL Digital Collections

The New York and Harlem Railroad

When the New York and Harlem Railroad (now Metro North) was incorporated in 1831 to better link the city with Harlem and Westchester County, Charles recognized the potential the railroad would have on Harlem’s development.

As an alderman of the Twelfth Ward, he pushed through the grading of Third Avenue from Tenth Street to the Harlem Bridge. At his own expense, he opened 129th Street across his property from Third to Eighth Avenue. He graded and paved it for a carriage way (129th Street was thus the first road north of Greenwich Village to be paved) and four-feet-wide sidewalks (the first sidewalks in Harlem). He also planted a double row of elm trees, making the street the most handsome in Harlem for more than 50 years.

This photo, which shows construction of the old Third Avenue el train in 1887 at 143rd Street, gives you a feel for what Harlem looked like near the Hall homestead only 130 years ago. NYPL Digital Collections

Charles Hall’s property fronted the old Harlem Lane, the predecessor of Saint Nicholas Avenue. The lane extended from Central Park and meandered up through northern Manhattan, serving as a popular racecourse for horse-drawn carriages in the nineteenth century. NYPL Digital Collections

The Demise of the Hall Mansion

The Panic of 1837 caught Charles Henry Hall and the Smith tea company off guard. One by one the mortgages on his property were foreclosed. In 1840, the mortgage on the homestead was foreclosed. Two years later, in 1842, his son reportedly committed suicide by shooting himself at the age of 25.

Over the years, a part of the Hall estate fell into the hands of a German named Geiger, who for many years operated a well-patronized garden (it was a favorite among children, who loved picking fruit from the trees). Advertisements in the New York newspapers through 1856 promoted the gardens as a great place for a rural ramble or for military companies to practice target firing (I’m not sure how those two things worked together).

Later, a man named Richards acquired the Hall mansion and greatly disfigured it by adding a third story. For a while he ran a sort of asylum and school for what one newspaper called “weak minded and wholly idiotic children.” The institution was not a success.

Charles Hall died on January 8, 1852. He was buried in the family vault in the rural cemetery at St. Andrew’s Church, then located on the southeast corner of present-day Park Avenue and East 128th Street. His wife died shortly thereafter that same year and was also buried in the vault. (Incidentally, when the church moved to its current address at 2067 Fifth Avenue in 1890, the bones of about 40 persons that had been buried between 1830 and 1873 were re-interred in a vault at Woodlawn Cemetery. The Hall’s bodies were not among the identified re-interments at Woodlawn Cemetery.

Could the remains of Charles and Sarah Hall still be buried under this vacant fenced-in lot on the corner of Park Avenue and East 128th Street, where there was once a rural church burial ground with about 293 vaults?

That same year, “324 choice and valuable building lots” on Fifth and Sixth Avenue, and on 131st, 132nd, 133rd, 134th, and 135th Streets were sold at auction. Advertisements for the auction stated: “The lots are all full size, beautifully situated for immediate improvement, and as the ground is free from rocks, dry, level, and graded by nature, it is admirably adapted for building purposes. There will not probably occur again within ten years, a sale where such safe, profitable and judicious investment of capital can be made.”

For some reason, the Hall mansion was not immediately demolished. Instead, a fourth floor was added to the grand old house and it was converted to a tenement house. However, in 1885, the the Board of Health declared it inhabitable. As The New York Times noted, it was then “filled with the poorest of people, and whole families crowded into one and two rooms.” The police were often called to the building, and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children took many children away from what had become a wretched place.

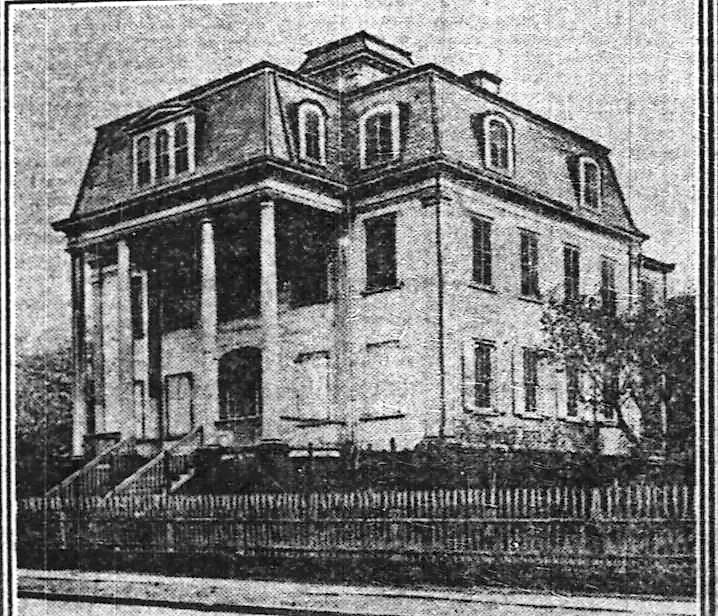

The Watt-Pinkney homestead at Seventh Avenue and 139th Street was still standing in 1911, 23 years after the Hall mansion was demolished. I imagine the Hall home may have looked very similar before it became a tenement house in the 1880s.

Demolition of the Hall mansion began in December 1888. Over the next few years, what had once been the magnificent home, gardens, ponds, orchards, and stables of Charles Henry Hall were all replaced by row houses and apartment buildings, where Mr. and Mrs. S.W. Watson lived with their German police dog, and Louise B. Hart made sure the people–and dogs–of Harlem had a proper funeral when they too passed from this earth.

The demolition of the old “Hall mansion” that stood for nearly one hundred years on the rocky elevation between 131st and 132nd Streets and Fifth and Lenox Avenues, was the severing of one of the few remaining links that composed the chain which connected the social side of the present Harlem with that of two score years ago, or less, in fact, for in the ears of the oldest Harlemite there still echoes the last few strains of a dying waltz, or the lively chords of the then “latest” music, to which the belles and beaux danced a merry quadrille.

Can we not picture to ourselves to-day the pretty spectacle our grandmammas and grandpapas, our dear papas and mammas presented, as with linked arms they strode across green fields to the scene of festivities, or perhaps seated in the family carriage they rolled over the unpaved roads noiselessly and approached the “Hall mansion,” or the Belden residence, at Third Avenue and 114th Street, through bowered driveways, each a mile in length, that led to the respective dwellings… But then came the march of improvements as steady as an army, and as rapid as the soldier’s double quick step. Farms were divided and subdivided, and orchards rang with the sound of the woodman’s axe, but genealogical trees were spared; so today Harlem boasts of many descendants of good old families.–New York Herald, February 24, 1889

Here’s an aerial view of the old Gabriel Furman-Charles Hall homestead today, courtesy of Google Maps.