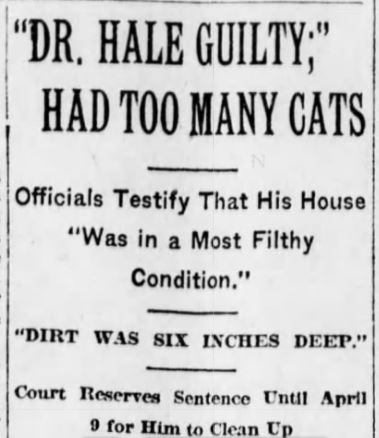

Dr. Hale and his wife Louisa often appeared in the New York newspapers for having too many cats.

Part I: Guilty of Having Too Many Cats

Many people ask me how I find all the stories for my Hatching Cat blog. One of the things I often do is search for keywords in the old newspaper archives that are available online.

For this story, I searched for news articles about “too many cats.” I came across this gem about Dr. William Henry Hale, the superintendent of Brooklyn’s public baths who got into some hot water with his wife and the law during several incidents involving too many cats between 1909 and 1917.

In March 1917, Dr. William Henry Hale was found guilty of maintaining his house, at 40 First Place, in a filthy condition. The Court of Special Sessions charged him with a violation of the health laws for keeping “a large number of cats” in his house and failing to clean up the premises. According to Dr. Albert Morton and Inspector Harry J. Maloney–the heath officials who had inspected the three-story brownstone in Carroll Gardens–the home was “in a most filthy condition” with dirt that was six inches deep.

The “filth” included bones, empty bottles, litter, and dirt that was several layers thick throughout the house, including the roof and front area-way. “It was so deep that we couldn’t tell if there was any carpet on the floors or stairways,” the inspectors told the court. The men also said they saw about 16 cats in the house during the inspection.

In a last-ditch effort to avoid the charges, Dr. Hale blamed the mess completely on his estranged wife, stating that he had not lived in the home for the past 20 months, and therefore, she was the one who was guilty of having too many cats.

“My wife insists upon keeping cats and they are ruining me. They have already eaten up more than the house has cost,” Dr. Hale told Justice Arthur C. Salmon. He also said that the offensive odor coming from the house was caused by a chemical disinfectant that was kept in the hallways.

Dr. Hale appealed the court’s decision, but the conviction was upheld in the Appellate Division on November 9, 1917. He was fined a whopping $25.

Dr. Hale Was a Cat Man

Dr. Hale was not lying when he told the court that his wife was a cat collector. However, he was not telling the whole truth. For at least a dozen years prior to this event, Dr. Hale had been an equal partner with his wife in cat hoarding.

Louisa Hale provided food and water to every stray cat in the neighborhood, However, Dr. Hale was not completely innocent; he was an equal partner with his wife when it came to cat hoarding. (This is not Mrs. Hale, but I love this vintage photo.)

William Hale, the son of Sylvester Hale and Nancy Arzelia Eames Hale, was born on August 20, 1840, in Albany County, New York. He received his law degree from the Albany School of Law in 1861 and his Doctorate of Philosophy from Yale in 1863 (he was reportedly only one of three people to have earned such a degree at that time).

After finishing school, William worked on the Chicago Board of Trade for a while, and then as a stock broker in New York. He also practiced law in Albany for a while before moving to Brooklyn around 1888.

William married his much younger wife, Louisa Gertrude Washington, on February 25, 1892. He began his civil service career as a clerk in Brooklyn’s Department of Buildings, and was appointed Superintendent of Public Baths by Brooklyn Borough President Bird Sim Coler in March 1906.

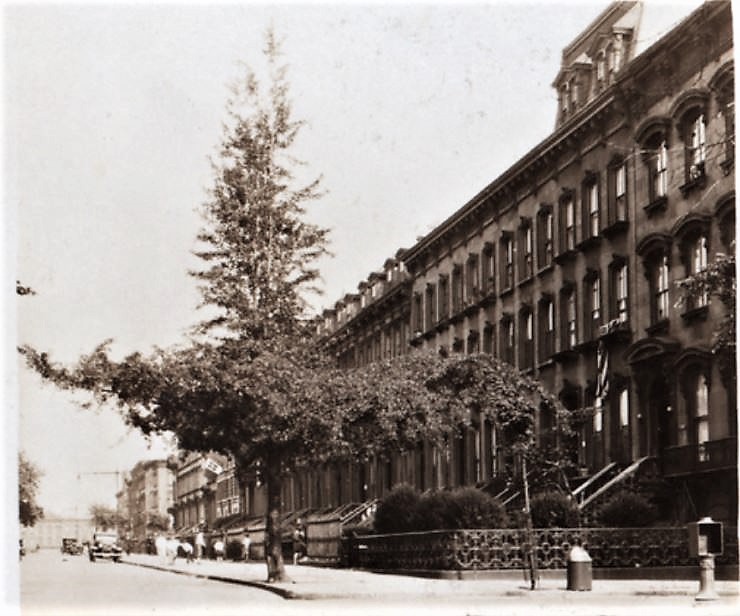

The Hale’s brownstone at 40 First Place was quite large, and since they did not have any children (or cats at first), they rented various rooms for many years. The rental ads said the rooms (including an alcove room on the second floor) were suitable for single gentlemen, and featured “all the modern improvements,” including hot and cold water, closets, gas, heat, folding beds, and a bath. The Hales also rented the back parlor, which was suitable for “gentlemen and their wives.”

The newspaper ads specifically stated that the house was clean. I’m going to assume that the cat hoarding did not begin until after 1900, which is the year the ads for the room rentals stopped appearing in the newspapers.

By the time Dr. Hale had taken charge of Brooklyn’s new public bath houses in 1906, I’m guessing that he had already been collecting cats for at least a year or more. Dr. Hale reportedly loved the cats, and he would always walk around the house at night with a lit match so he wouldn’t step on any of them. One time he even told his neighbors that he wanted to build a zig-zag fence around his house to offer more fence space for them. (They reportedly talked him out of it.)

According to an article in the New York Times on January 8, 1905, the Hales entered nine “reformed bootjack dodgers” in the New York Cat Show at Madison Square Garden. The “nine tramp cats of Brooklyn,” including cats named Snooks, Teddy Gold, and Ida Saxton McKinley, took 13 blue ribbons at the show.

Here’s what the article said about the Hales and their cats:

Both Mr. and Mrs. Hale are interested in cats and have reclaimed many a furry outcast. They gather in the homeless and friendless felines, feed and pamper them and teach them good manners. Mrs. Hale has taken in many a depraved vagrant prowling around on back fences and fast approaching the city dump and trained him to be somebody in the feline world. Among the cats under her care which she has rescued from vagabondage were nine that had come to know and practice all the little niceties of cat etiquette. They had learned not to wash their faces in public and to keep their coats smooth and their whiskers neatly combed.

Mrs. Hale was so proud of the reformation which had taken place in these once dissipated and abandoned creatures that she decided to enter them in the cat show held at Madison Square Garden last week. She had no idea of playing a joke on the show people. Nor did she expect any of her entries to win a prize. She merely hoped some persons would take a fancy to the cats and give them good homes. Joke or not, however, the nine Hale cats carried off thirteen prizes. They won purely on their merits as cats, Mrs. Hale declares. Four of them were bought by admirers.

Teddy Gold, of orange coat, formerly a swashbuckling freebooter, who picked his living out of area ways and kitchen windows in the neighborhood of Court Street and First Place, was one of the prize-winners. Another was “Ida Saxton McKinley,” so named because she wandered into the Hale house on Mrs. McKinley’s birthday. She was exhibited with her six-months-old kitten. Tittlemouse by name. Snooks, another Hale entry, with a shady past won in a walk out of his class, which should have been for nondescripts. Emmy Lou [who had beat out German champion cats Schell and Langsam at the Atlantic City Cat Show] and Novie also simply ran away from the aristocrats in the gray tabby class.

Altogether it was regarded as a great triumph for the slums of Brooklyn catdom, and the celebration on the back fences of the borough last night was kept up until the sympathetic smile at the pale new moon was lost in the flooding light of dawn.

A Cat Named Emmy Lou

Emmy Lou was a tiger cat with green eyes and broad black markings. When she arrived at the Hale house sometime around 1905, Dr. and Mrs. Hale were already taking care of 14 cats, some of whom were quite sick. (Many of these waif cats, including one with large orange eyes called Gladdie, won prizes at the Brooklyn Cat Show.)

The Hales reportedly attracted the cats to their cat asylum by leaving out a bowl of hot milk and choice cuts of meat on their front stoop for any stray tabby that happened to come by. (As one newspaper noted, “The tramp cats must have had a code of passing good news, because the number of felines that come to their house is almost limitless.”) Although the cats stayed outdoors during most of the year (the Hales had a large, colorful tent in their backyard to provide shelter), they would be allowed indoors in the cold winter months.

Mrs. Hale told a news reporter how Emmy Lou had come into her life:

“At 4 o’clock on Monday morning I saw Emmy’s little face pressed against the window pane. I took her in and gave her all the warm milk she could drink. After that she used to come and see me early every morning. When the extremely cold weather came I adopted her.”

In March 1905, Mrs. Hale gave Emmy Lou to Mrs. J.C. Lathrop, who was going to take the cat to Buffalo, New York. According to Mrs. Hale, Mrs. Lathrop was waiting for the train at the 125th Street Station of the New York Central when a train came along on the other track and frightened the cat. Emmy Lou jumped out of her basket and ran up the tracks toward 125th Street. The station men tried to catch her, but she escaped down the street.

40 First Place, Carroll Gardens

The Hales lived at 40 First Place, which was one of a long row of 19th-century, three-story brownstones with basements in Carroll Gardens, like these pictured here on First Place near Clinton Street in 1930. This recent video of 46 Front Street will give you an idea of what the home may have looked like before all the cats moved in and took over. New York Public Library Digital Collections

The name Carroll comes from Charles Carroll of Maryland, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who never lived in Brooklyn, but who is deserving of recognition nonetheless. During the Revolutionary War, Carroll led a regiment of 400 men that tried to regain from the British the Old Stone House, which was a strategically placed farmhouse on the Gowanus Creek (Gowanus Canal).

About 300 of Carroll’s men were killed in the attacks, which took place during the Battle of Brooklyn in August 1776. A street, a park, and finally an entire neighborhood were named in honor of him.

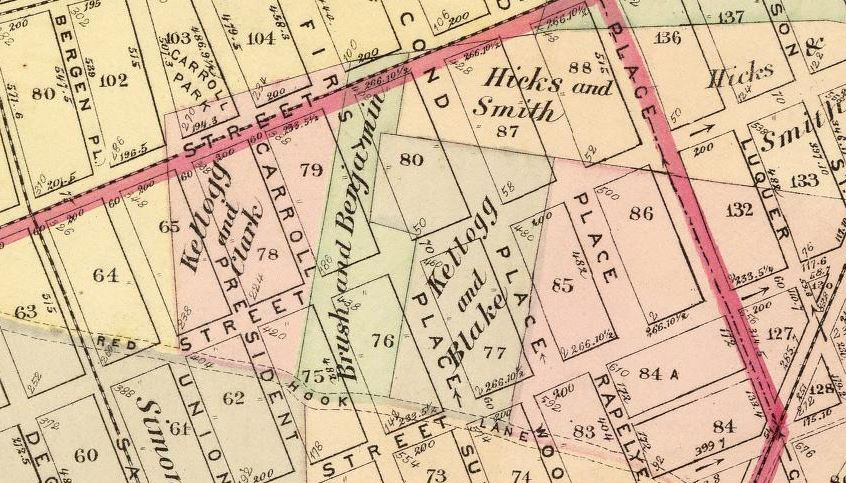

40 First Place was constructed sometime during the 1850s on a large parcel of land formerly owned by real estate investors Edward Kellogg and Anson Blake.

An 1850s article in the Brooklyn Eagle sums up the block as follows:

“First Place — the high and rolling ground known of old as Bergen Hill, which overlooks Gowanus Bay and New York Bay, and takes the sweep of the clear ocean breeze, has been laid off into blocks of more than ordinary depth, for the building of mansions for the rich, and is likely to become the court end of the city. A number of splendid buildings with deep court yards in front, and built of brown stone, have already been erected, and preparations are in progress for more. The streets intersect Court Street, and are called Places, to distinguish them from the vulgar herd of common streets. The aristocracy of wealth have at last shown their good sense in seizing on, and appropriating this splendid location.”

Here is 40 First Place today (with the holiday decorations). I don’t see any cats in the yard.

In Part II, I’ll tell you why the fur was flying at 40 First Place after Dr. Hale placed an anonymous “cats for sale” ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1908. We’ll also explore a brief history of the Brooklyn public baths.

.