According to the Seamen’s Church Institute of New York (one of the city’s oldest maritime establishments), cats and dogs were the most popular mascots on ships in the good old days. Seamen were especially fond of cats, as they brought good luck to a maiden voyage. The Institute also seemed to favor cats, and in fact had numerous feline mascots at its New York City headquarters in the early 1900s.

The special relationship between sailors and cats dates back thousands of years. Although ship cats were primarily responsible for killing the rats that gnawed at the ship’s ropes and provisions, they also provided companionship and a sense of security for men who were often away from loved ones for long periods of time.

Seafaring cats were especially popular during wartime, when almost every ship had at least one cat. Although some of the cats were born on the piers of Manhattan or Brooklyn, many were refugees that had traveled to New York on the various steamships taking part in the war efforts. American sailors would oftentimes “liberate” the cats of other foreign ships and make them their own.

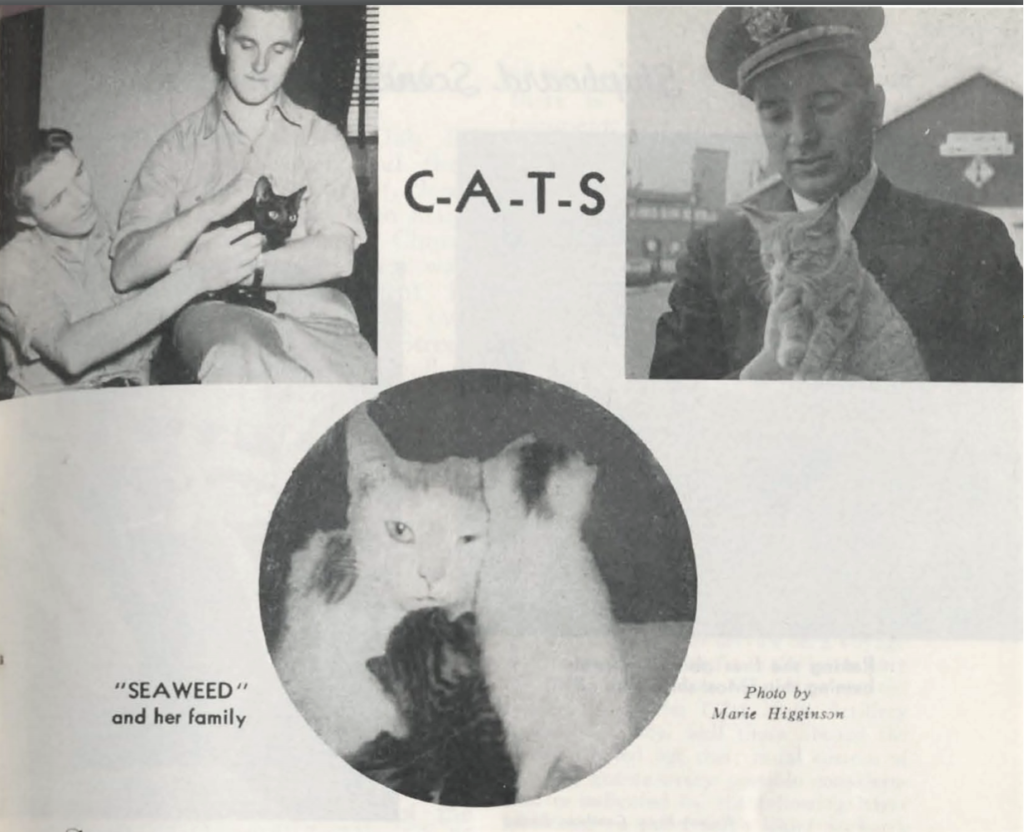

During the 1930s and 40s, the Institute had several cat mascots — the men called them “The Cat of the Moment” — including Queen Hannah, King Mickey, Stormy Weather, and Bosun. Bosun’s mother, Seaweed, drifted in on a Liberty ship in 1946 and made her home under the desk of game room hostess Christine Albert Hartmann.

According to The Lookout, on February 9, 1946, Seaweed gave birth to four kittens shortly after she arrived at the Institute. The news of the birth was called “a blessed event on the waterfront.”

The men originally named the kittens Ditto, Quote, Unquote, and Comma because of the white markings on their noses. The mariners hoped to groom the new cats as ship mascots for four new cargo vessels of the United States Lines: Onward, Rapid, Defender, and Whistler.

Mrs. Hartmann set up a basket for the cat family in the game room with a curtain and a sign that said Caternity Hospital. Twice a day, she’d pull back the curtain to let the sailors play with the kittens. The mariners would advise Mrs. Hartmann on the cats’ diets and would offer to bring them to sea on their ships.

Shortly after the kittens’ birth, a contest was held to find better seafaring names for them. James F. Sweeney, a fireman and water tender, came up with the winning names: Fogbound, Skipper, Hatches, and Sea Wolf, who was later renamed Bosun. (Bosun is the ship’s officer in charge of the crew.)

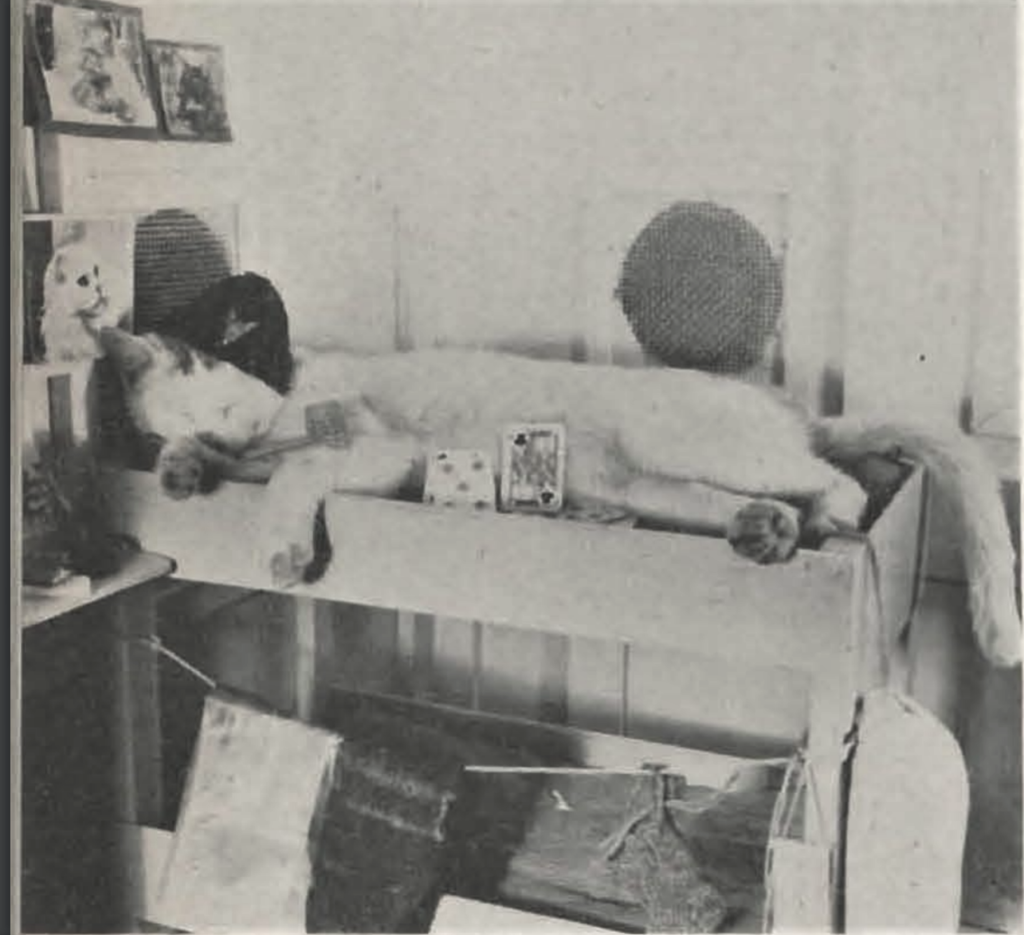

Of the four kittens, Bosun was the only one who enjoyed stretching out lazily in his bed made by sailors and lapping up egg on toast for breakfast every day. The other cats were lured to the sea: Fogbound went to Greece, Skipper headed to Italy, and Hatches went to the Pacific.

In October 1946, Bosun appeared at the Brooklyn-Long Island Cat Club show at the Hotel Granada (268 Ashland Place) in Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the cat as a bum who not only didn’t know who his father was, but who was leading the Life of Reilly amid all the other pampered and more exotic felines at the show.

“An unimportant white color, Bosun is not a cat’s cat. He’s for men and rough talk,” the reporter wrote. His cage was described as being gaudy with pin-up pictures of lady cats in “provocative poses.” None of the other 150 cats in attendance had decorated cages.

Bosun did not compete for any prizes; not only was he not qualified, but his mom, Mrs. Hartmann, was one of the judges.

Boson retired from the Seamen’s Church Institute in 1948 and went to live with the Hartmanns on their farm in Long Island. He made one more public appearance at the Motor Boat Show in 1949, pictured below.

The Seamen’s Church Organ Cats

Although some of the Institute’s cats were described as being “not very religious,” one unnamed female cat was especially fond of the chapel.

In June 1939, Mrs. Janet Ruper, house mother and head of the missing seamen’s bureau, told The Lookout about a cat who spent most of her time in the chapel. She especially enjoyed climbing into the organ chamber and meowing loudly during Sunday services. (Church organs were very popular with Old New York cats.)

One day, the cat gave birth to two kittens in the church organ. “And do you know what?” Mrs. Roper exclaimed. “Those kittens were coal black except for a pure white cross on each of their backs!”

A Brief History of the Seamen’s Church Institute

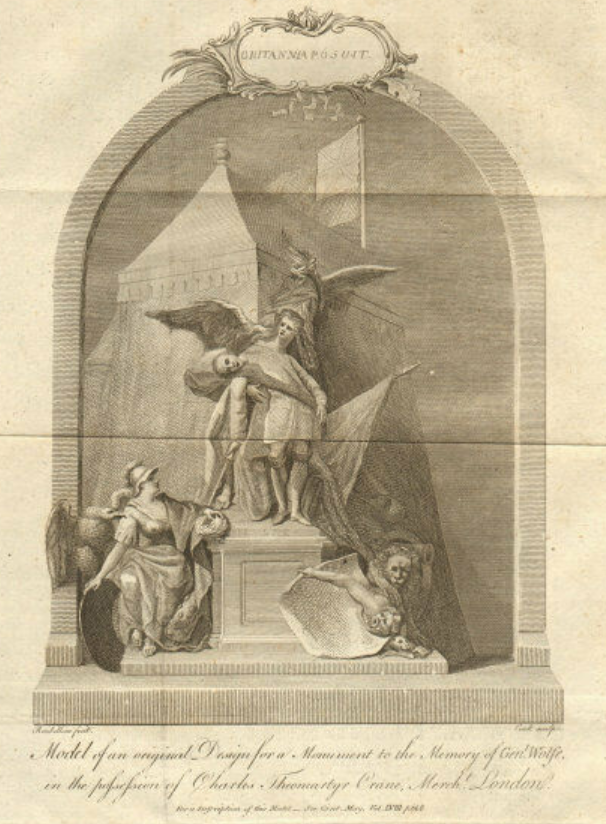

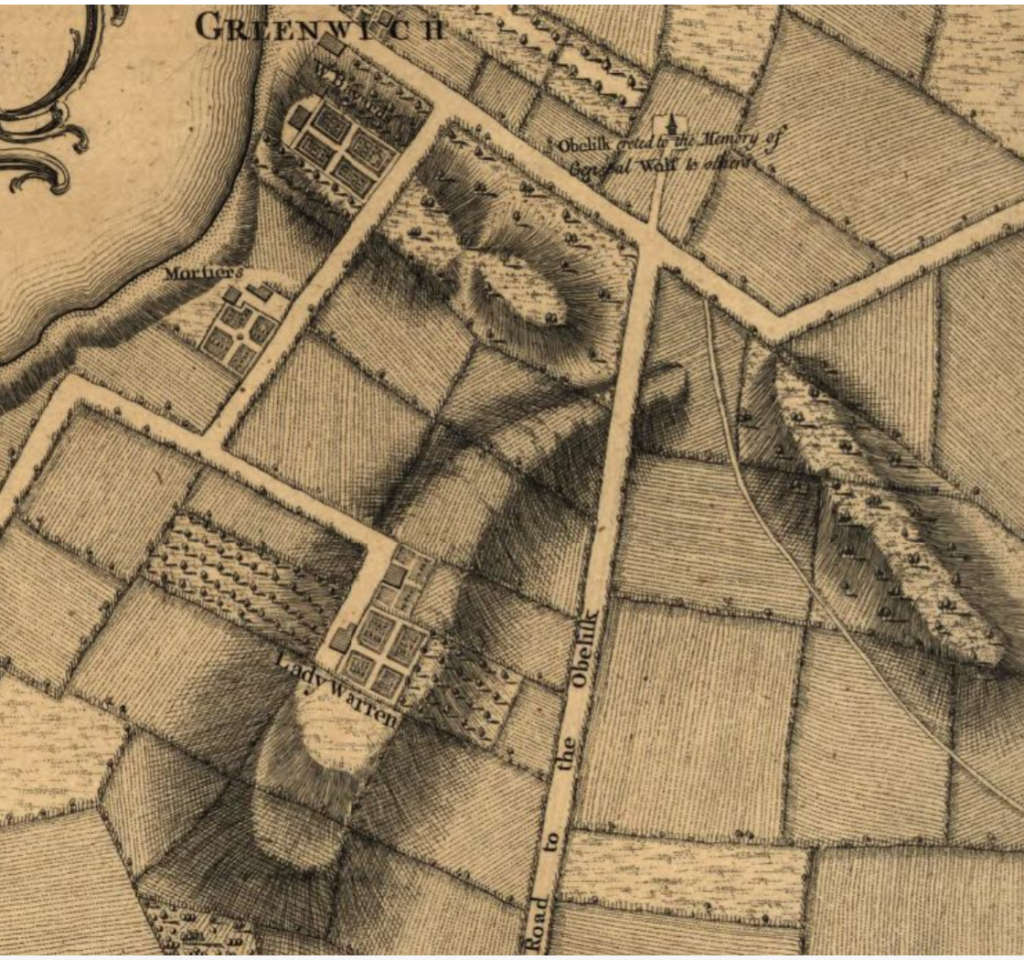

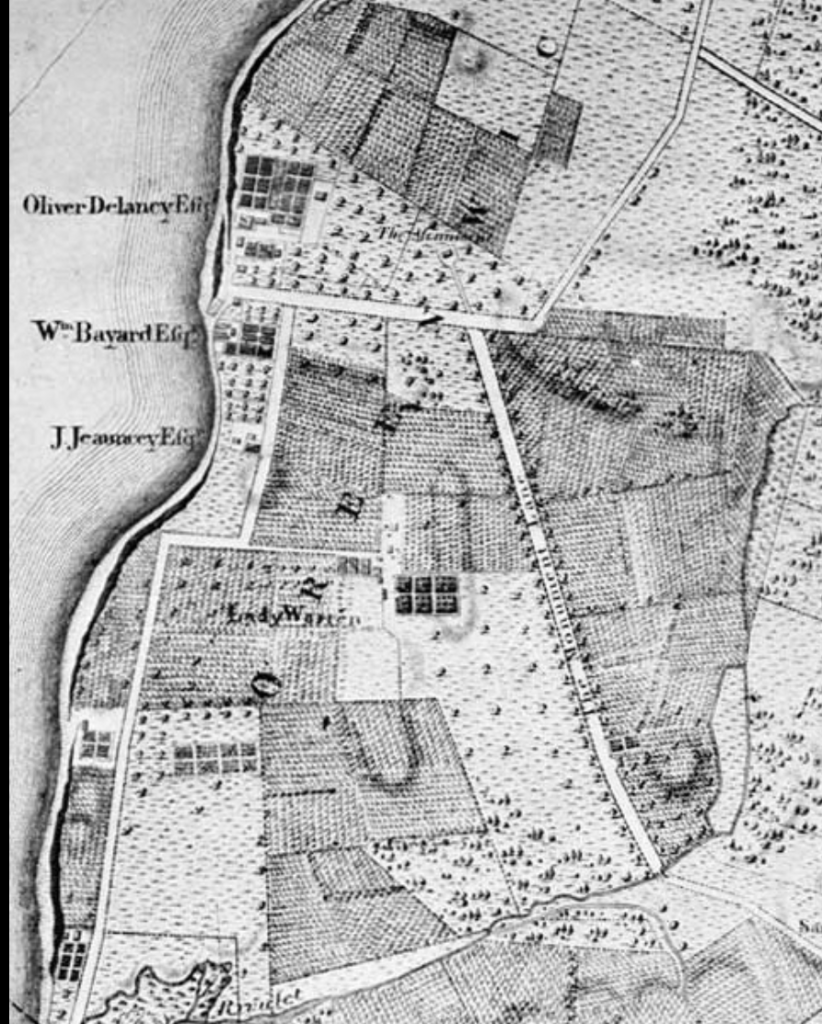

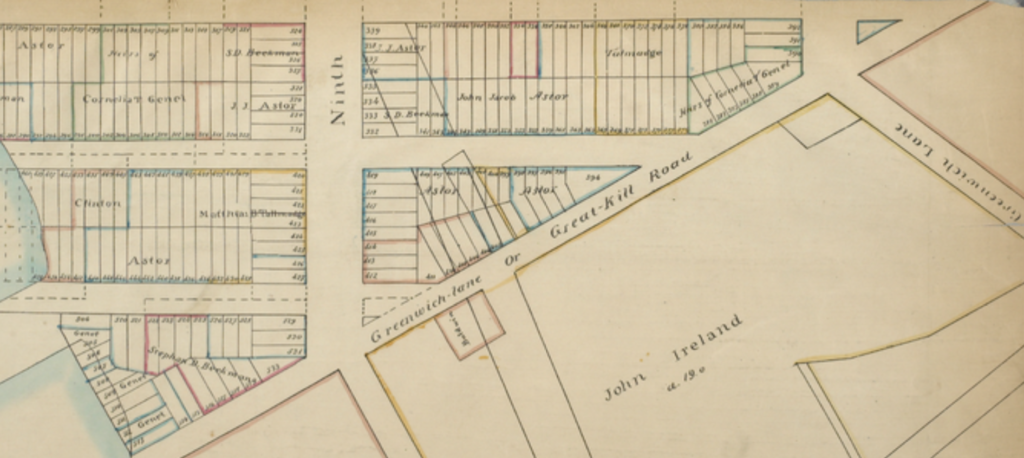

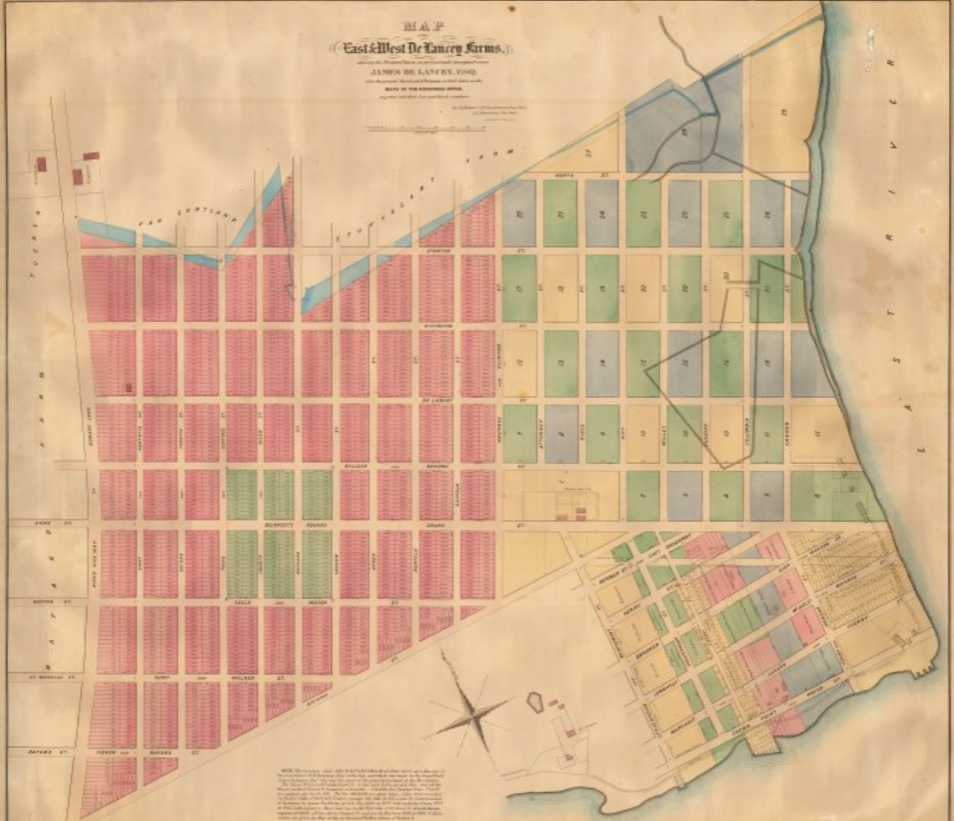

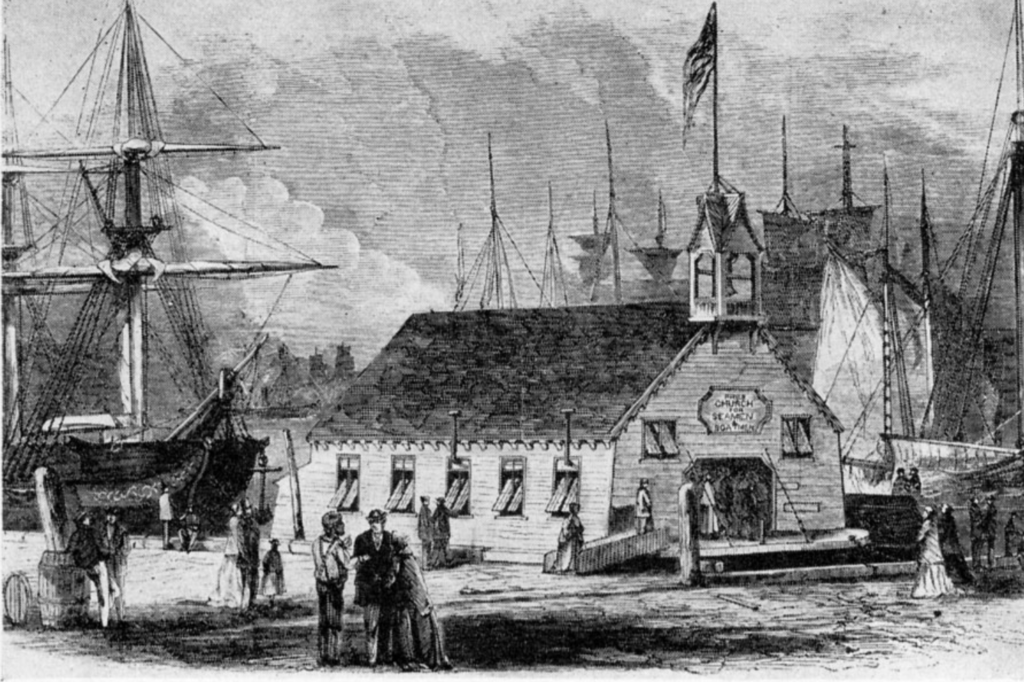

In 1834, a small group of Episcopal men founded the Young Men’s Church Missionary Society on the Lower East Side waterfront. Their first Chaplain, Reverend Benjamin C.C. Parker, presided over church services for seafarers in the Floating Church of Our Savior.

This unique Gothic church was built atop a barge in 1844 and docked, like a large boat, at the foot of Pike Street on the East River. This floating chapel provided not only a place of worship but also a place where seafarers from around the world could feel at home.

In 1846, the Society built its second floating church, the Floating Church of the Holy Comforter. This church was built at the foot of Dey Street on the Hudson River (right about where One World Trade Center is today) to accommodate seafarers and local residents on the west side of the island. The Holy Comforter provided services until 1868.

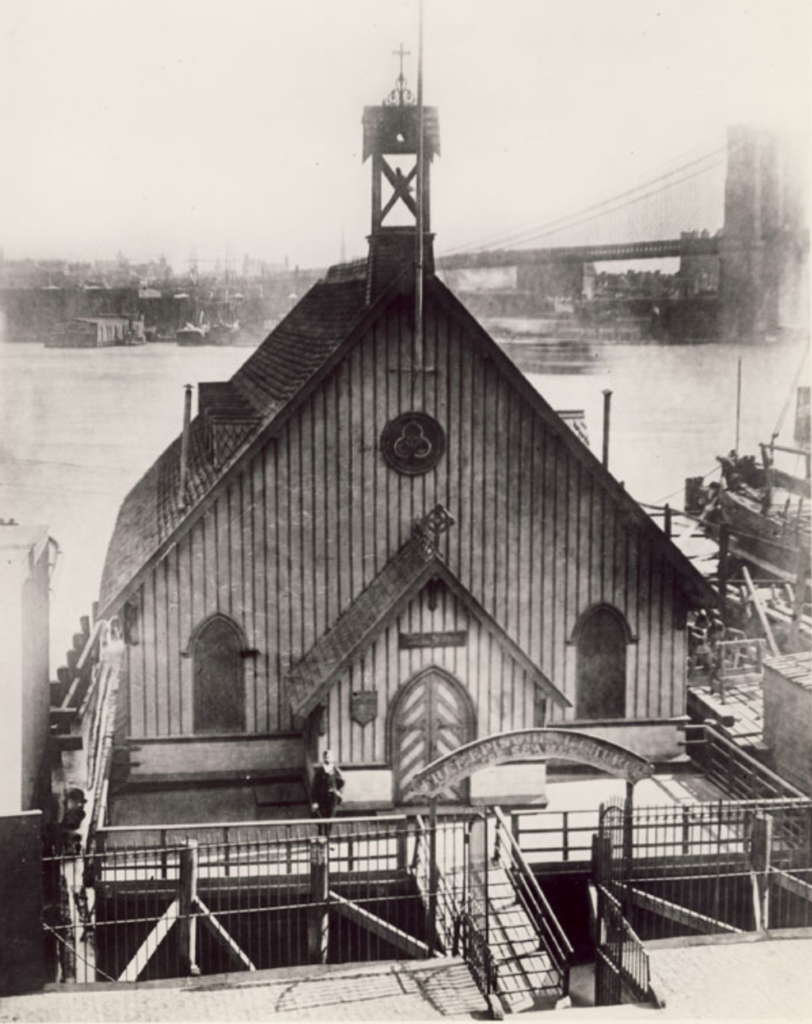

The Floating Church of Our Savior burned down in 1866 and was replaced with a new floating church in 1870. The second East River church was in use until 1910, after which it was towed to the Kill Van Kull at Mariners’ Harbor in Staten Island and renamed All Saints’ Episcopal Church.

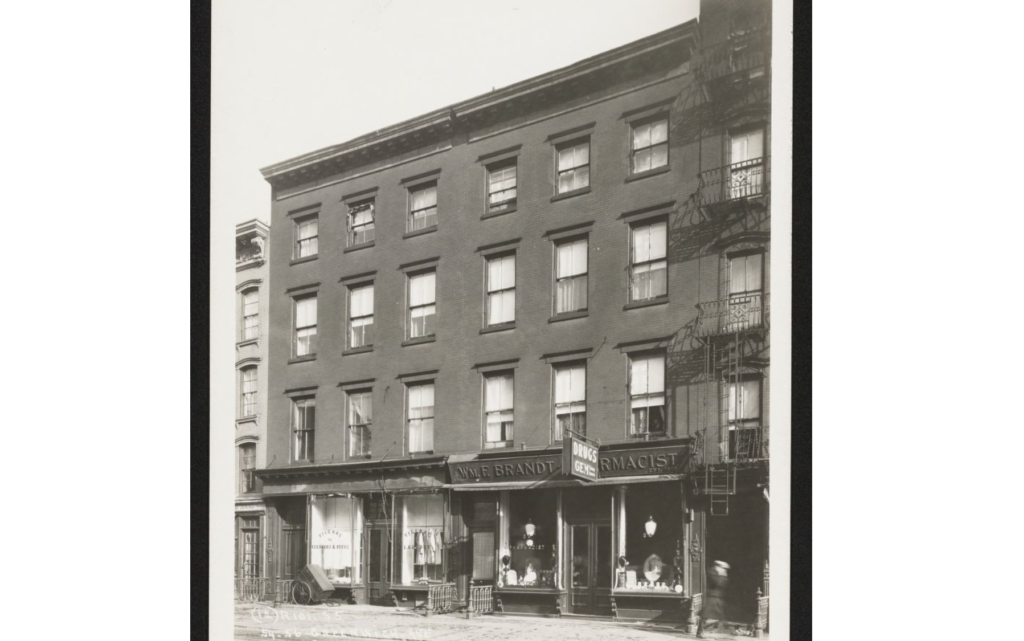

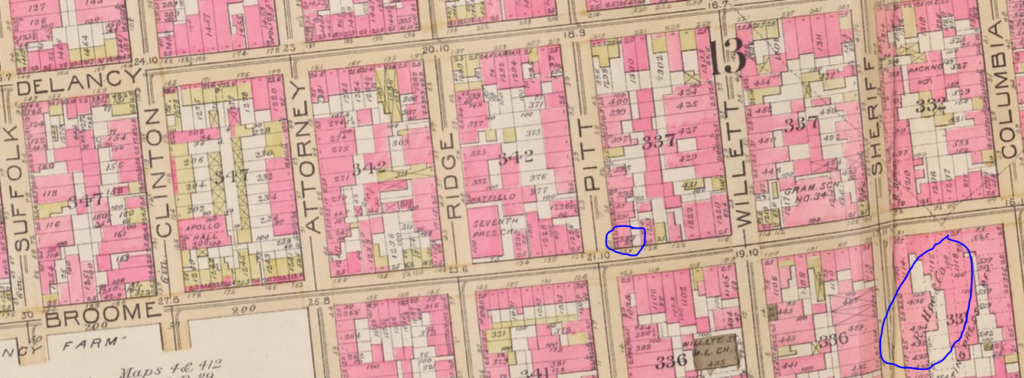

Throughout the 1800s, the Society built several facilities for mariners, including a reading room at Coenties Slip, a mission house at 34 Pike Street, and a sailors’ boardinghouse at 52 Market Street.

In 1906, the Society formally changed its name to the Seamen’s Church Institute of New York. Two years later, Franklin D. Roosevelt joined the Board; he remained on the Board until his death in 1945.

Ironically, the Seamen’s Church Institute laid the cornerstone of its new “million-dollar home for seamen” on April 15, 1912. This was the morning of the sinking of RMS Titanic. When the RMS Carpathia arrived in New York with the survivors, the Institute delivered clothing and kits to the surviving Titanic crew members.

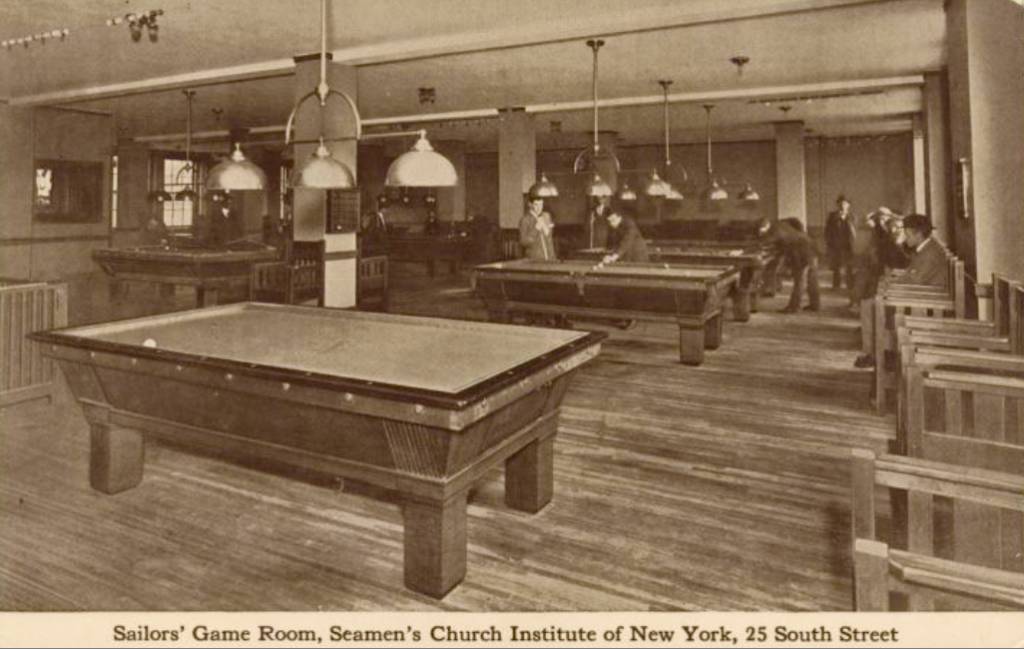

The new twelve-story building at 25 South Street accommodated up to 580 seafarers in dormitory-style rooms. The headquarters also housed an employment bureau, savings bank, medical clinic, reading room (stocked with foreign newspapers and magazines), writing room, chapel, and basement storage area for the men to store baggage while at sea. A sign in the lobby read, “This Institute is willing to help men who help themselves.”

One of the memorable features of the building was its main door, which was guarded by “Sir Galahad” beside a bell that had been salvaged from the passenger steamer Atlantic, which had wrecked in 1846 on Long Island Sound. The bell rang out the hour and half hour.

In 1917, a memorial to the Titanic was placed on the roof of the building along with a light and a raised ball. The ball was lowered at noon to help ships anchored in the harbor set their clocks. The building was razed in the 1960s, but the Titanic memorial still exists at the comer of Water and Fulton Streets.

In 1968, the Seamen’s Church Institute moved into a new 18-story building at 15 State Street in Battery Park. The old cornerstone, ship’s bell, and several bronze memorial plaques were installed at the new headquarters. The Institute sold this building in 1985 for more than $29 million.

The next home for the Seamen’s Church Institute was located at 241 Water Street in the Historic Buildings section of the South Street Seaport Museum. Following the attacks on 9/11, this building was transformed into an emergency relief station for rescue workers, where thousands of meals were served and truckloads of donated supplies were distributed to the workers.

Ten years later, the Seamen’s Church Institute of New York sold its headquarters building on Water Street and donated (permanent loan) its archival collections to CUNY Queens College. The Institute is currently headquartered on the 26th floor at 50 Broadway.

Sadly, I doubt that any modern-day wayward cats ever drift into this new building…