Topsey, Turvey, Pickles, Grover, and Buffles were just some of the prized pets who made their home in the Whitby Kennels at the old Bergen Homestead on Flatbush Avenue.

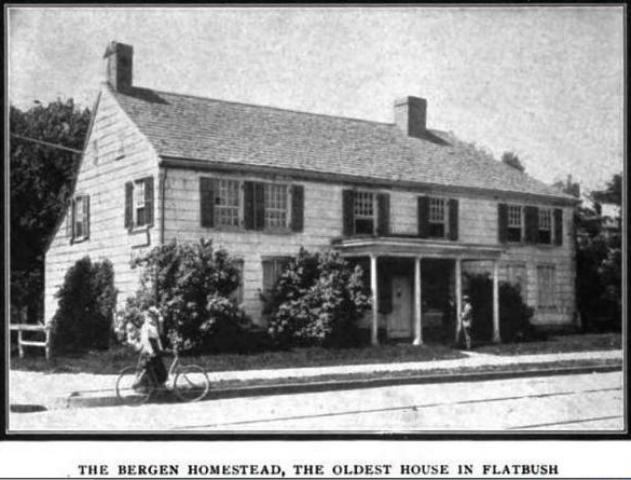

One of the most widely known and attractive of the old fashioned revolutionary residences, in which the town of Flatbush abounds, is the old Bergen homestead on Flatbush Avenue, above Grant Street. This ancient pile has become a decided attraction to the sightseers who travel out that way, principally on Sundays, not on account of its historical importance, but because of the Whitby dog kennel, which has been located there for about two years. –Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 1893

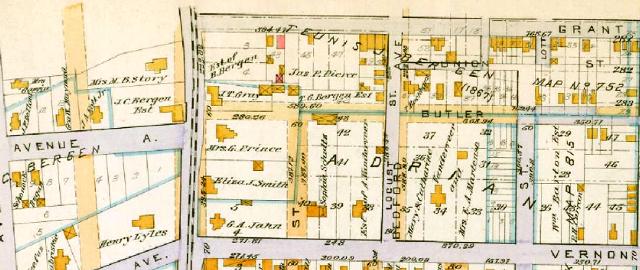

In 1891, a once prominent lawyer from Rye, New York, leased the old John C. Bergen homestead at 972 Flatbush Avenue, just below Grant Street (today’s Snyder Avenue), at the corner of Avenue A (today’s Albemarle Road).

Once a man of considerable wealth, Hurlbut Chapman (aka Hurlburt or Herbert), the son of stockbroker Henry P. Chapman and Rebecca Hurlbut, had reportedly lost his fortune and so decided to earn a living by operating a dog and cat kennel in Brooklyn. The Whitby Kennels also served as a summer boarding house for the pets of the rich and famous.

During the next two years, the Whitby Kennels became very well known to many Brooklynites who loved finely bred dogs and who thought of the kennels as one of the attractions of the town.

The first thing that attracted the attention of passersby was the number of handsome dogs which were tethered in the two-acre fenced-in yard. The tethering system was considered quite novel and practical: Long wires were stretched from tree to tree, upon which ran lose rings to which the dogs were fastened by chains ranging in length from 50 to 100 feet long.

Each wire was far enough apart to prevent the dogs from mingling or quarreling, allowing up to a dozen dogs to run in the yard at a time. (With over 30 dogs at the kennels, the dogs had to take turns on the tethers.)

Blocks of wood were strung from the wires about six feet from each tree in order to prevent the dogs from getting tangled around the trees.

In the rear of the yard, to the left of the house, was a stable and barnyard where little pups were kept together until they could care for themselves. It was here that Hurlbut Chapman also kept any new dogs that he received until he could thoroughly examine them and test their disposition before allowing them to mingle with any other dogs.

Special dogs, such as James and his son Grover — two black poodles owned by James Gordon Bennett, Jr. — were kept indoors, on the first floor of the old homestead.

The dogs, each valued at $500, were given to Gordon by a prominent New York woman, and were trained to do difficult and funny tricks. According to one article published in the New York World in 1893, the dogs were trained by Captain Farley of Hook & Ladder Company No. 15 at Old Slip and Pearl Street.

Prize-winning show dogs, including fox terriers Sparkle and Pickles, blue Skye Terrier Buffles, Irish setters Flashlight and Sunray, and Ruth, a smooth-coated St. Bernard that was reportedly as large as a cow, were also kept indoors at the Whitby Kennels. They had full run of the house, and were often caught napping on the couches.

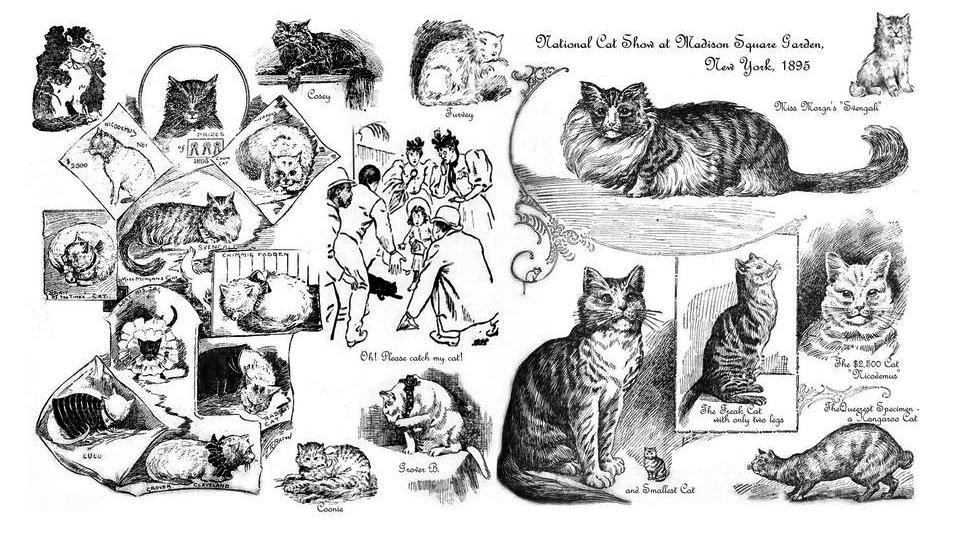

Hurlbut, with some assistance from his brother William and a female cousin, also bred Angora cats. It was said that he had five of the most handsome Angora cats in the country: Turvy (the sole Tom cat, who took a prize at the first National Cat Show in 1895), Fluff and Topsy (who also took a prize at the cat show), Puff, and Pansy.

The cats had their own cages on the front porch; they also spent time indoors in the drawing room, which took up half of the homestead’s lower floor and featured a piano that the cats liked to play on. Several litters of Angora kittens occupied a room on the upper floor.

On June 25, 1893, the New York World reported that Hurlbut had a group portrait taken of all his dogs and cats at the Whitby Kennels. How I’d love to find this photo!

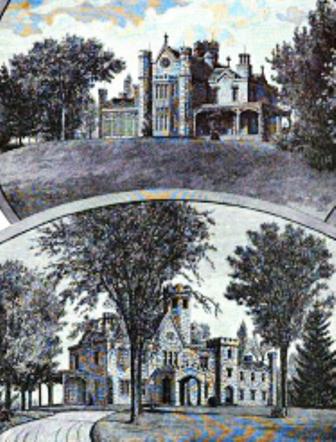

The John C. Bergen Homestead

The oldest house in Flatbush is the Bergen homestead, built by Dominie Freeman, who was mainly responsible for the spiritual welfare of early Flatbushers. Generous in its proportions, faces full upon the main thoroughfare. Original side shingles remain intact; heavy wooden shutters on the second floor had been replaced by modern window blinds. A simple porch supported by 4 plain columns, and a still more simpler door, with brass knocker and long panels, attract the attention of the most unlearned wayfarer. Many generations of Bergens have stepped out into the world from this same plain door that stares at the passing trolley-cars, and more than one romance has woven its magic charm around the long, substantial pile.—The Book of a Hundred Houses, 1902

Built sometime around 1735, the old homestead — sometimes called the Freeman homestead — was home to Dominie Bernadus Freeman, a native of Holland who served as pastor of the Reformed Dutch Church in Flatbush (aka Midwout, or the middle woods) from 1705 to 1741. Back then, Flatbush Avenue was known as Main Street, which previously was an old Native American trail that led from the Jamaica Bay to the East River.

The home was constructed of wood and featured low ceilings with heavy wooden crossbeams. The foundation and fireplace were constructed of bricks reportedly brought over from Holland. The front door facing Flatbush Avenue opened to a long hall with a square sitting room to the right and a dining and living room to the left.

The Revolutionary War Period

Dominie Freeman reportedly enjoyed good wine, and when he came to America, he brought with him a considerable quantity from Holland, which he kept in a wine cellar in the west wing of the house. Reportedly, the British Red Coats overindulged on Dominie’s good wine during the Battle of Long Island in August 1776.

According to one story, Dominie Freeman was a Whig — the political party that believed in separating from England — and a neighbor by the name of John Ruble was a Tory, and thus, did not want America to separate from England. Ruble told the British of the sparkling wine in the cellar, and even directed them to the house.

Dominie Freeman reportedly hid the wine in the eaves of the house, and then took to the woods with his family, including his only child, Anna Margaretta, and his son-in-law, David Clarkson. The British eventually found the wine and for three days took part in a drunken revelry. By the end of the party, the Red Coats had all but passed out under the trees in the yard. Had the American officers known about the effects of the “find” they might have utilized the knowledge and changed the course of history.

David Clarkson and his bride took possession of the homestead during the Revolution, and at one time the home was used as a military prison and later as a hospital after the battle.

Sometime after the war ended, the home and farm came into the possession of Hendrik Suydam, who in turn willed the property to his daughter Gertrude. In 1785, Gertrude married Cornelius Bergen, the son of Hans (Johannes) Bergen of Norway and Catryntie De Hart. Cornelius served as the Sheriff of Kings County from 1794-98, and from 1800 to 1805.

For over 100 years, the property stayed in the Bergen family. John C. Bergen, the son of Cornelius and Gertrude, inherited the home and large farm as per his mother’s will dated April 25, 1838. John and his wife, Belinda Antonide, had several children — Cornelia Lozier Bergen, Mrs. Abraham Lott (Gertrude), and Mrs. William H. Story (Maria) — who continued to own and lease the house until about 1900.

The End of Whitby Kennels and the Bergen Homestead

In March 1896, Hurlbut’s cat Marie — a brown and black Angora from Paris — was one of several cats to escape from the second annual National Cat Show at Madison Square Garden II. She was captured shortly thereafter, and was awarded a silver bowl for best long-haired cat in her class.

Three months later, Hurlbut Chapman died at the age of 38 (pneumonia) at his home in the old Leggett estate on Mamaroneck Avenue in White Plains, New York.

By this time, the Whitby Kennels were located in what was once the Village of Kensico (now Valhalla), just north of White Plains, and were being managed by Chapman’s female cousin. In addition to boarding cats, dogs, and horses, the cousin also reportedly had a small pet cemetery on the grounds, where, in 1896, one cat and three dogs were buried.

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, the old Bergen homestead — still owned by the heirs of John C. Bergen — was leased and occupied by Secretary William H. Brown of the Williasmsburgh Fire Insurance Company. William Brown and his wife were quite social, and many a party and wedding took place at the home during the 15 years that they lived there.

Then on January 19, 1901, workmen began tearing down the house. Luckily, the family was able to salvage a cannonball that had become implanted in the walls during the Battle of Long Island, and a window on which were engraved several names of patriots who fought in the Revolution.

In 1905, the Chelsea Improvement Company developed Prospect Park South, a 50-acre tract that included part of the old John C. Bergen farm. Then in 1906, the Abels-Gold Realty Company constructed six brick structures on the property fronting Flatbush Avenue, each with stores on the lower levels and apartments above. These buildings are still standing today.

Just across the street at 977 Flatbush Avenue was the old Teunis Bergen homestead, built around 1835. Over the years, the home’s large parlor served as a place of worship for several Brooklyn churches, including the Presbyterian Church, Baptist Church of the Redeemer, and St. Mark’s Methodist Church. The home also served as an annex for the nearby Erasmus Hall High School.

In 1903, Spencer C. Cary purchased the home, which at that time was owned by the Empire Dairy Company. Cary sold the home to the Borden Milk Company in 1910, and soon thereafter the old home was razed.

William Fox’s Albemarle Theatre was constructed on the site of the Teunis Bergen homestead in 1920. The building was damaged in a fire in 1984, but was subsequently purchased by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who still use the building as their Assembly Hall.

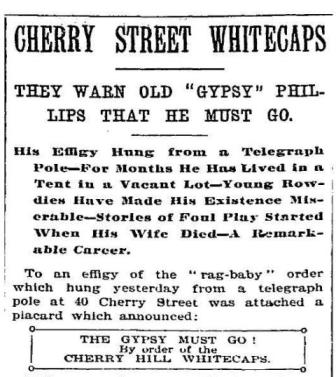

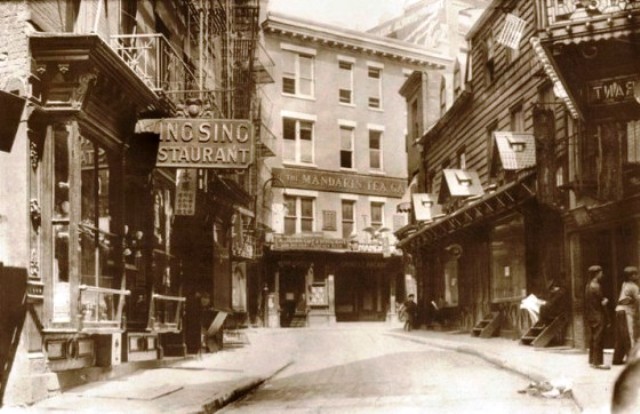

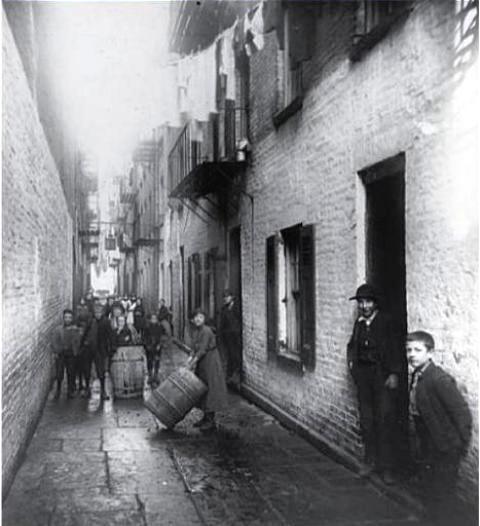

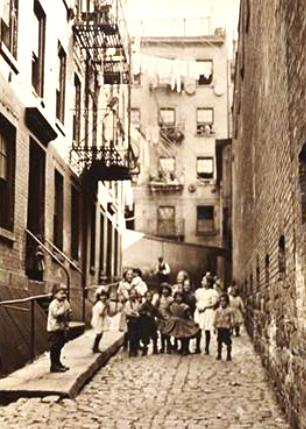

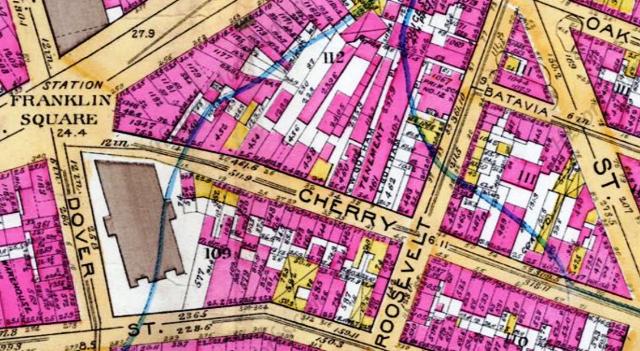

Morgan and Clarissa S. Phillips lived at 40 Cherry Street — the white rectangular lot south of Roosevelt Street in this 1891 atlas of Manhattan. Just to the left is the massive Gotham Court Tenement, constructed in 1850. The long, narrow alleyways West Gotham Place and East Gotham Place are on either side.

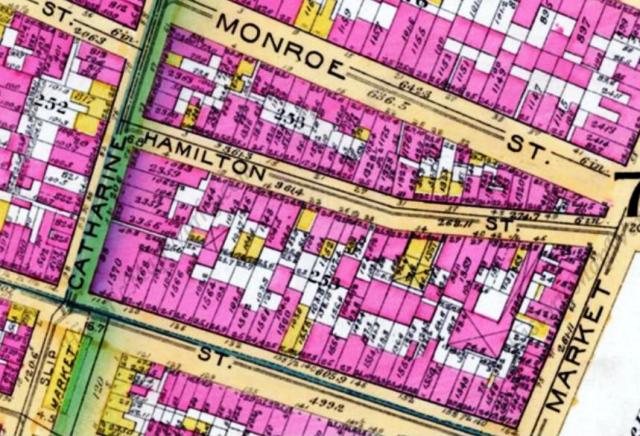

Morgan and Clarissa S. Phillips lived at 40 Cherry Street — the white rectangular lot south of Roosevelt Street in this 1891 atlas of Manhattan. Just to the left is the massive Gotham Court Tenement, constructed in 1850. The long, narrow alleyways West Gotham Place and East Gotham Place are on either side. The Phillips were living in a tent in a vacant lot at 30 Monroe Street (the white lot just above the bend in Hamilton Street) when Albert died in August 1892. Today, this square block between Cherry, Market, Catherine, and Monroe streets is the site of the

The Phillips were living in a tent in a vacant lot at 30 Monroe Street (the white lot just above the bend in Hamilton Street) when Albert died in August 1892. Today, this square block between Cherry, Market, Catherine, and Monroe streets is the site of the  In 1934, when this photograph was taken, 30 Monroe Street was once again an empty lot, so to speak; the four-story tenement built in 1893 had already been demolished to make way for the new

In 1934, when this photograph was taken, 30 Monroe Street was once again an empty lot, so to speak; the four-story tenement built in 1893 had already been demolished to make way for the new  Clarissa Phillips died at 33 Cherry Street, seen from the back in this

Clarissa Phillips died at 33 Cherry Street, seen from the back in this