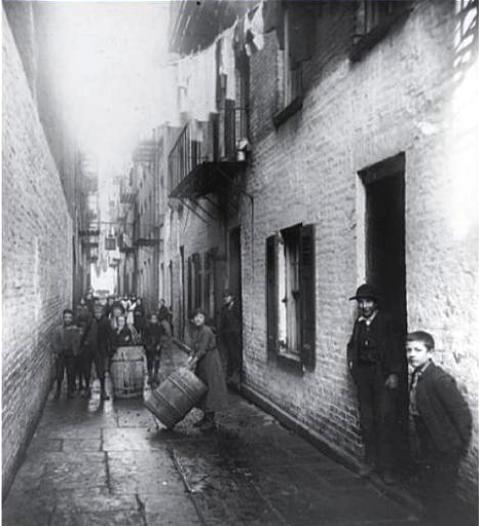

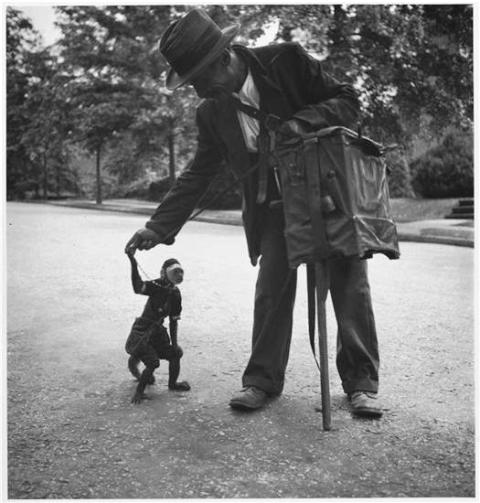

If you’re like most people reading this, when you hear the term “organ grinder” you immediately picture a man of Italian descent playing the bulky instrument with a Capuchin monkey at his side collecting coins in a tin cup. I would not expect you to envision an Irish organ grinder like Timothy McGrath.

It may be stereotypical, but you can’t be blamed for thinking this way. By 1880, according to author Tyler Anbinder in his book Five Points, nearly one in 20 Italian immigrant men in New York City’s Five Points neighborhood were organ grinders. And most of them had a companion of the primate persuasion.

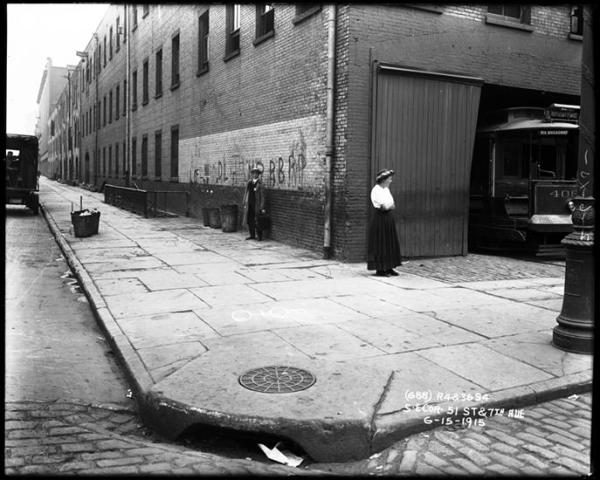

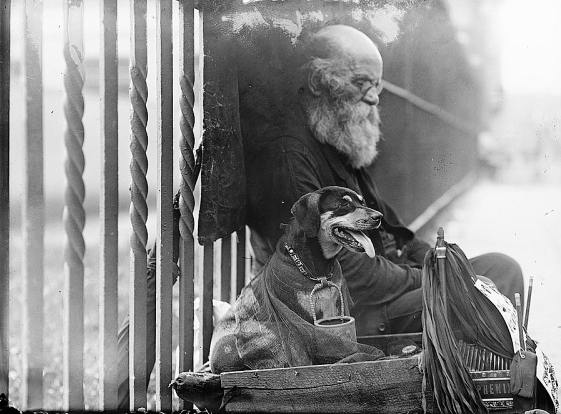

One organ grinder who broke the mold was Irishman Timothy McGrath, who, for over 10 years, played his hand-organ along 7th and 8th avenues in New York City’s Tenderloin District. Instead of a monkey, Timothy had a grizzly-haired Skye terrier who would sit on top of the organ wrapped in a blanket and holding a basket in his mouth. Women passersby simply could not resist placing a few coins in the basket, even when their male companions scorned their actions.

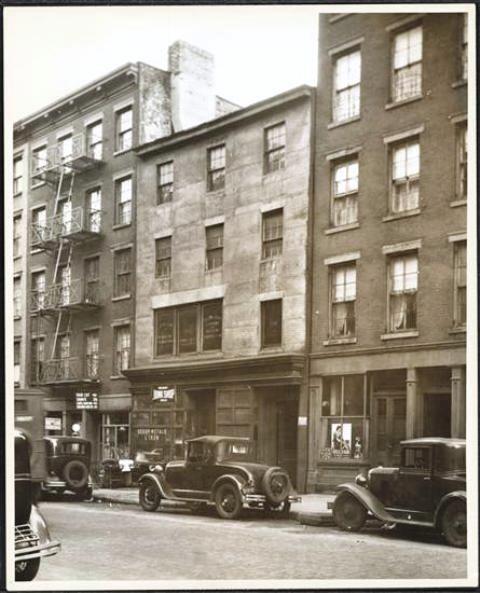

Like many street performers in those days, Timothy was nearly blind. But he was able to get around the neighborhood and live on his own in a small third-floor room at 402 West 38th Street.

Timothy moved into the small room around 1881, shortly after his wife and two children took ill and died within weeks of each other in the family’s small brick home, also on West 38th Street. (They may have died of diphtheria, which killed almost 5,000 Manhattan residents in 1881.)

Save for his daily organ playing, Timothy lead a very secluded life for the next 20 years. In fact, his only true human companion was James Brown, a tailor who had a shop on the ground floor and also served as the building’s janitor.

Timothy was no doubt familiar with the neighborhood because he had spent all his teenage and adult years living in the West 30s along 9th Avenue. It was here he attended the New York Institution for the Blind from about 1855 to 1860, receiving not only general education lessons but also taking part in a pilot manufacturing workshop in which adult residents made basketry, mattresses, and other items for sale.

Timothy McGrath’s Neighborhood

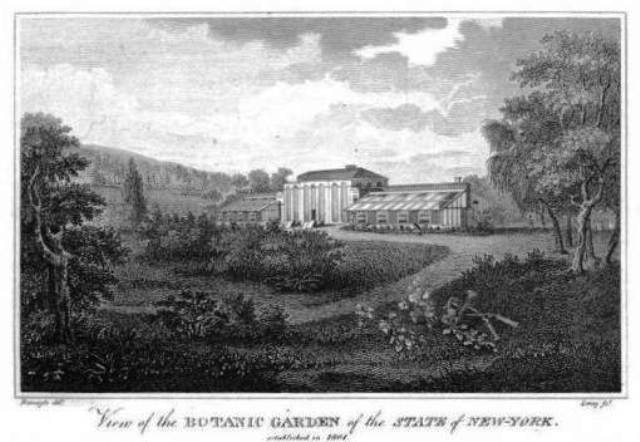

The history of the Old New York neighborhood in which Timothy the organ grinder lived – today located on the edge of Hell’s Kitchen and the Garment District – goes back to about 1639, when it was leased by Dutch settler Hendrick Pietersen van Wesel. (Hendrick’s farmhouse was identified on the 1639 “Manatus Map” as farm number 15.)

In 1647, Governor Willem Kieft granted this farm to Adriaen Pietersen van Alckmaer, and following the death of his heirs (around 1657), the land reverted to the Dutch East India Company.

The Weylandt Patent

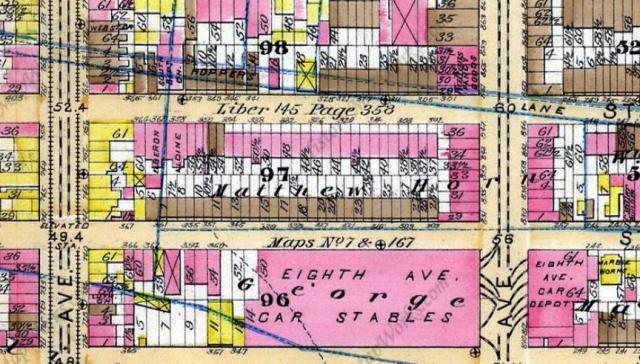

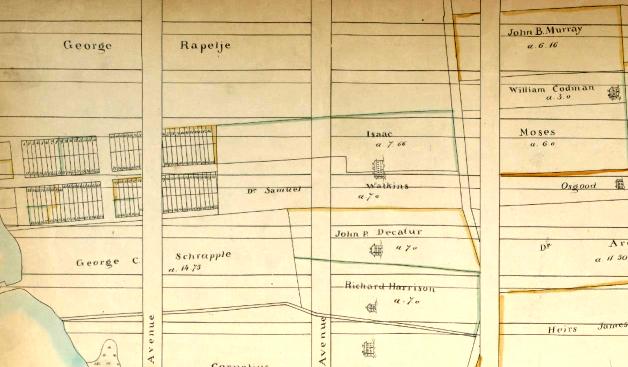

In 1668 the first English governor, Richard Nicolls, granted the land now known as the Weylandt (meadow) Patent to three Dutch farmers for the purpose of pasturing their cattle and horses. The patent encompassed 300 acres and was bounded by the Hudson River, the Bloomingdale Road (Broadway), the Great Kill (where three streams converged at 10th Avenue and 40th Street), and Clapboard Valley, a small semi-circular fenced-in meadow with a little stream between 28th and 30th Street.

The three recipients of the Weylandt Patent divided the area into six parallel lots, running east to west, for the entire width of the grant: Cornelis van Ruyven (Lots 1-2), Allard Anthony (3-4), and Paulus Leendertse van der Grift (5-6).

Fast-forward 100 years to 1757, when Lot 5 (about 38th-42nd Street), now owned by Mathias Ernest, included a dock at the river and a small wooden house that was once a roadhouse and now used for the manufacture of glass bottles. (Although Ernest’s glass venture failed, the entire neighborhood came to be known as the Glass House Farm through much of the nineteenth century.)

By 1780, most of the patent land was owned by Rem Rapelje and Jacobus Van Orden, who had inherited several southern lots from his grandfather, Johannes van Couwenhoven. When Jacobus died in 1782, his lots went to his daughter Madgalena, the wife of Thomas Tibbet Warner.

Two years later, Warner conveyed the land, which included a large house and barn, to John Watts, who in turn sold it in 1795 to Isaac Moses and Benjamin Seixas. (Talk about real estate flipping!)

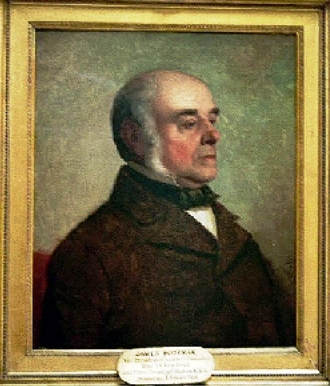

In 1832, wealthy iron merchant James Boorman purchased the old Isaac Moses farm from Moses L. Moses and adjacent lots from Samuel Watkins. (By now, the original six lots of the Weylandt Patent had been subdivided into numerous building lots for future development, but most of the land had yet to be improved.

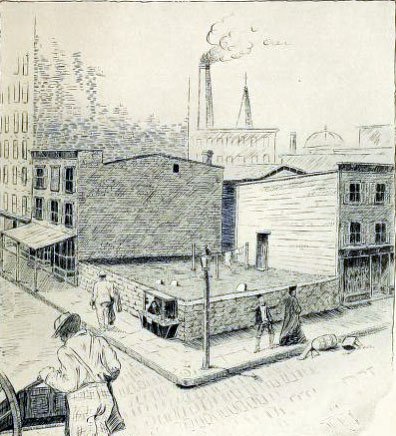

The roads in this part of Manhattan were still not paved, and city water, sewer, and gas lines did not yet exist.) Boorman named his new estate Abington Place.

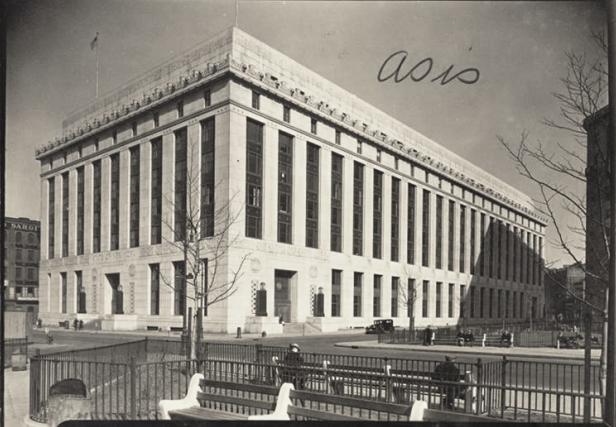

The New York Institution for the Blind

At the same time all these real estate transactions were taking place in the 1830s, three prominent New Yorkers were in the process of starting a school for blind children — first in a private home on Mercer Street and later, at 62 South Street. On March 15, 1832, the New York Institution for the Blind, under the leadership of founders Samuel Wood, a Quaker philanthropist; Dr. Samuel Akerly, a physician; and Dr. John Dennison Russ, a philanthropist and physician, held its first class for three blind children. Two months later, the school had six students.

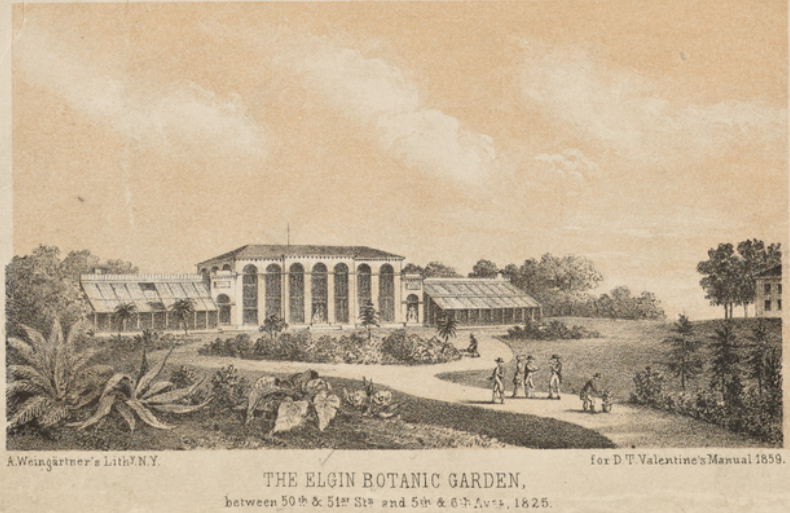

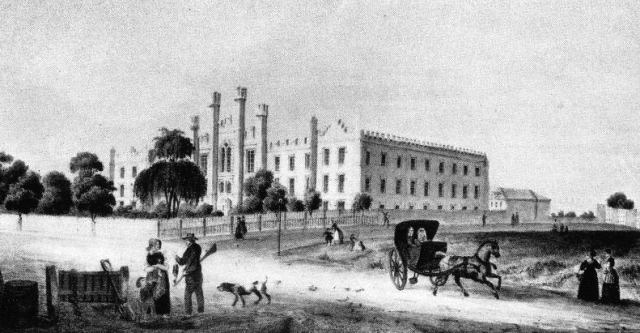

Looking to greatly expand the school, the Institution sought benefactors to donate land or money. James Boorman responded by offering to lease to the school, for nine years, 32 lots with buildings, including a large, two-story marble mansion that was unoccupied. The rent: one peppercorn per year.

As described in the New York Evening Post, August 15, 1833:

The main building on the premises is a large substantial two story house, 100 by 54 feet, situated on a rising ground overlooking the Hudson River. There are also two stone kitchens apart from the main building, and a well of good water near the house.

The ground is now in good order, under cultivation as a garden, and contains a little’ over two acres. The situation is stated to be one of the pleasantest on Manhattan Island, in the immediate vicinity of the city, and offers fine air, good soil for cultivation, a shady grove and flower garden, with wide and level paths.

The house is very large, two stories high, with a spacious attic, abundantly large enough for a workshop and place for exercise in bad weather, while the distance from the City Hall is only about three miles.

Classes began at the new school building on October 10, 1833. By the end of 1834, the school had 26 pupils.

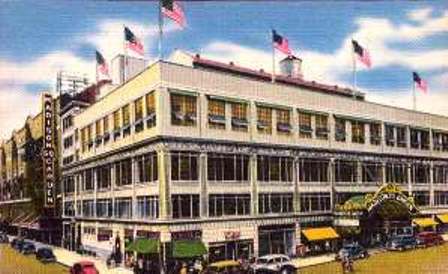

In 1837, the Institution purchased the western half of the large lot and began construction on a stone Gothic revival building. The original marble estate was demolished in 1840, and in 1850, a three-story brick workshop called the Manufacturing Department was erected on the site of the former estate. It is here Timothy McGrath received occupational training and made products for which he received about $300 after graduating the school in 1860.

The Passing of Timothy McGrath, the Irish Organ Grinder

In January 1901, the Irish organ grinder took ill. James Brown, his only companion, started checking on him daily to make sure he had enough food to eat (his diet consisted of bread and condensed milk).

About a month later, the dog, whom I call Timothy II, passed away, reportedly from starvation. For several days later James tapped on Timothy’s door to see if he needed more food, but each time Timothy said, “No, nothing. I have plenty of bread left for several days.”

On February 9, 1901, Brown got no answer when he knocked on Timothy’s door. He summoned a policeman, who broke down the door and found the organ grinder dead. An ambulance surgeon said Timothy, who was 58 years old, had died from the cold and lack of nourishment.

The big surprise came when police opened a tin box that they had found in the room. Inside were two bank books (Emigrants’ Savings Bank and Bank of Savings), showing credits totaling $15,000. They also found the deeds for a house on 40th Street, off Fifth Avenue, two lots near Greenwood Cemetery, a life insurance policy, and deeds for a lot and monument in Calvary Cemetery.

Timothy II the dog had obviously collected a lot of pennies in his basket over the years he worked as the mascot for an organ grinder.

According to news reports, Timothy McGrath had a brother who had two daughters and a son who worked as a letter carrier. But even after his story was published in several New York newspapers, no one came to the city morgue to claim his body or his property.