NYPD Mounted Heroes, Part II

I once wrote about two New York police officers who were killed in the line of duty while patrolling the streets of Brooklyn on a horse named Bulb. Now I’d like to share a happy story about Harry, a wonderful horse who served with the Prospect Park Police from 1893 to 1901 and who won several blue ribbons at the annual Brooklyn Horse Show.

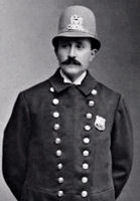

At 16.1 hands tall, Harry was one of the largest horses in the Mounted Unit at the time. The bay gelding was a familiar figure in Prospect Park, and was well-loved by “big and little folks alike” who walked and wheeled or rode and drove about the park grounds. For eight years, he and Patrolman Henry T. Hilton were a team, whether on the job or showing off their skills at the Riding and Driving Club’s popular horse shows.

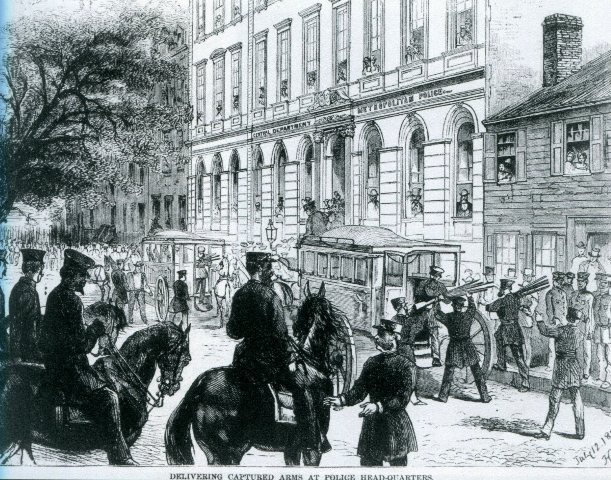

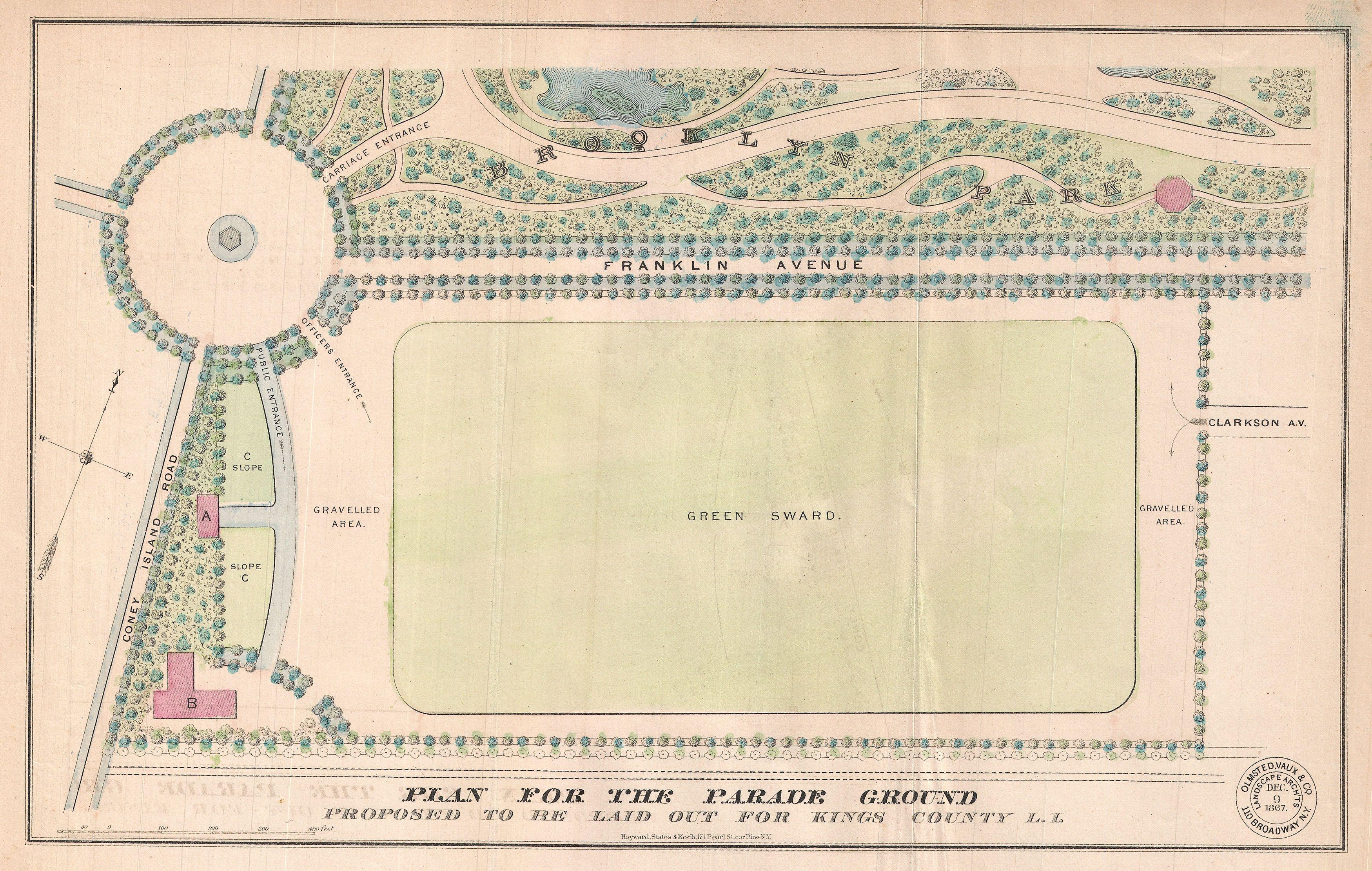

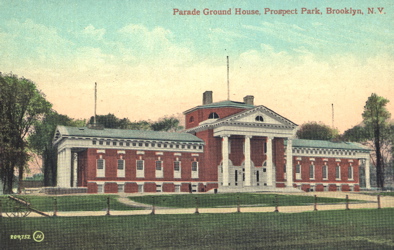

The Prospect Park Police – also once known as the 173rd Precinct and later the 73rd Precinct – was assigned to duty in an around Prospect Park, exclusively. Their territory was about 625 acres, and included the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and the Parade Grounds.

Prospect Park was always crowded with bicycles, horse-drawn carriages, and pedestrians, which kept the dynamic duo of Henry and Harry busy. According to news reports, Harry was a natural at chasing runaway horses, and had a knack for knowing when a horse had passed beyond the driver’s control. He enjoyed the pursuit, and when the fugitive was stopped he’d rub his velvet nose against Hilton’s arm.

One day in October 1895, Harry and Patrolman Hilton caught two runaways in Prospect Park. In the first pursuit, they stopped the horse of W.T. Swain, who lived at 122 Van Buren Street. This horse had bolted on Swain and his two female passengers, throwing them all from the wagon on East Drive.

A few hours later, Harry and Henry stopped the horse of T.C. Bowers, of 602 Van Buren Street. Bowers and his wife were thrown from their wagon when it collided with another. Unlike with car accidents, all of the victims in these horse accidents received only bruises.

Riding and Driving Club of Brooklyn

In 1889, 30 of Brooklyn’s most prominent sporting men, lead by young banker Albert H. Smith, decided to establish an equestrian club near the bridle paths and open spaces of Prospect Park. The men purchased a large, 4-acre triangular parcel of land along what was then called Sportsmen Row, just west of the Grand Army Plaza and bounded by Butler street (now Sterling Place), Plaza Street, and Vanderbilt Avenue.

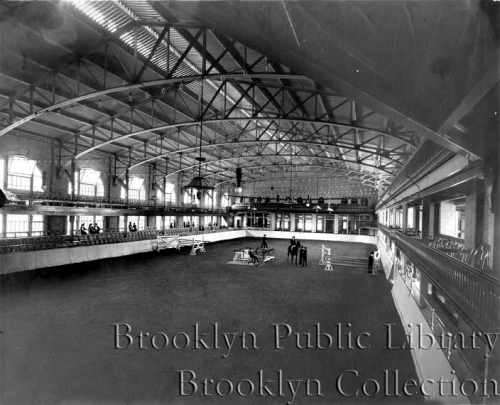

They hired the renowned architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White (of Madison Square Garden II fame) to design a clubhouse, riding ring, and stables for 200 horses. The club was officially incorporated on June 19, 1889, and the clubhouse opened in 1891. Click here for a more detailed look at the club’s history.

The Riding and Driving Club of Brooklyn was not just a club for men, but also for ladies, giving what the press called “a distinctive social turn.” The clubhouse provided lounging, smoking, billiard, and card rooms for the men, while women had access to reception and dressing rooms.

Although women had no voice in the management of the club, they were eligible for membership and could pay initiation fees when there was no male representative in the family. In addition to being a social club, the Brooklyn Riding and Driving Club also hosted frequent horse shows, including the annual Brooklyn Horse Show, indoor polo matches in Brooklyn armories, and other equestrian events.

The first officers and directors of the club included Albert H. Smith, president; Henry K. Sheldon, VP; William Nelson Dykman, secretary; and John S. James, treasurer.

Just as it does today, corruption reared its ugly head among those in power: In the fall of 1890, Albert Smith was arrested and charged with forgery for doctoring stock certificates – adding zeros to the share amounts – and siphoning the money into his personal account. Unlike today, however, the greedy banker was actually punished for his white-collar crime and sentenced to 17 years at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York.

The Prospect Park Police Exhibition at the Brooklyn Horse Show

On May 5, 1899, the Mounted Police performed what the Brooklyn Eagle reporter called a “spectacular drill” at the seventh annual Brooklyn Horse Show. Two platoons — 32 men commanded by Sergeant Egan of Manhattan — went through all sorts of cavalry maneuvers during their half-hour performance, beginning with the walk in single file and working up through a variety of tactics.

Patrolman Henry Hilton won the first-place blue ribbon and a $25 cash prize, Patrolman Robert Uhl of the 64th Precinct took the red, and Patrolman James Lannigan of the Prospect Park squad took yellow.

By 1899, Harry and Henry were veterans of the Brooklyn Horse Show and accustomed to taking the blue ribbon. The pair also took first place in the Mounted Park Police Exhibition in 1895 and 1896. In the former show, Duke, ridden by Patrolman William Vanderbeck came in second and Joe came in third with his partner, Patrolman John Tennant.

Harry Retires

In April 1901, the police department determined that Harry was too old for police work, so they took him out of service to spare him “the excitement of park police duty…and the heartbreaking strain which accompanies every dash to head off a runaway.” He was purchased by Michael A. McNamara, long-time captain of the Prospect Park Police, and spent the rest of his life at McNamara’s “palatial stable” in Englewood, New Jersey.

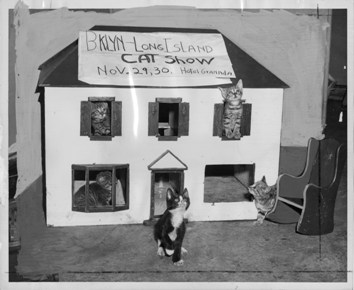

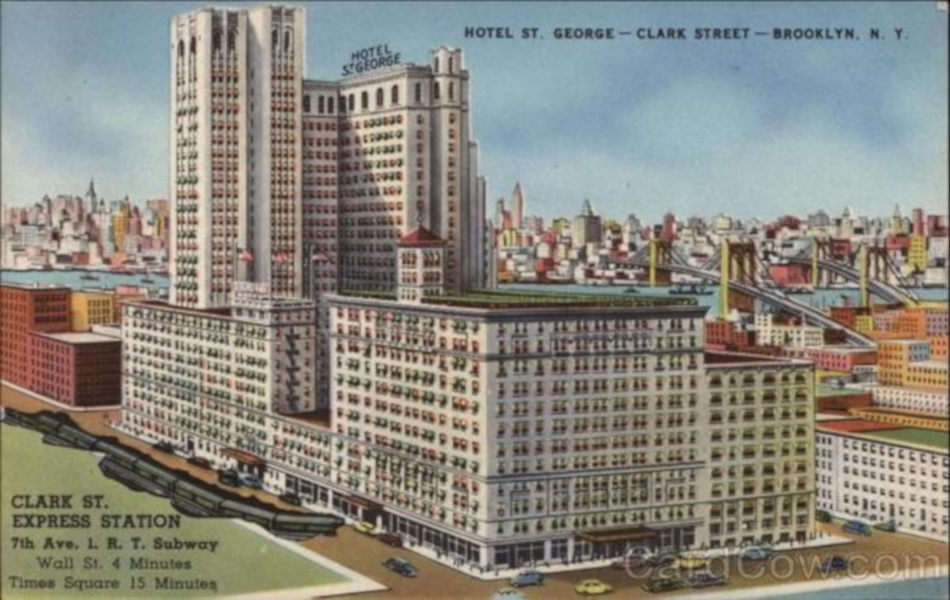

The first meeting of the BLI Cat Club was held in the Tower Room at the Hotel St. George.

The first meeting of the BLI Cat Club was held in the Tower Room at the Hotel St. George.